Did Neanderthals practice cannibalism?

Bones found in Asturias show evidence they were eaten by fellow hominids

Around 50,000 years ago, deep in a forest in what is now Asturias, in northern Spain, a family of around a dozen members was slaughtered and their remains eaten by cannibals. The bones lay briefly on the ground, but were then washed down into a cave during a storm. And there they lay, scattered on the cave floor, untouched through the centuries, until in 1994, cavers came upon the gruesome relics.

It was initially believed that the bones belonged to Republican guerrillas, who were supposed to have hidden out in the caves during the Spanish Civil War. But police forensic scientists soon confirmed that the bones were much, much older.

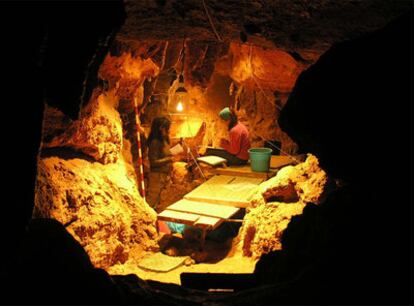

The cave complex, known as El Sidrón, has since become one of the most important sites on the planet for the study of our distant ancestors the Neanderthals, who spread across Europe and Asia from about 240,000 to 30,000 years ago. Researchers have found almost 2,000 bone fragments in the cave, some of which have yielded DNA.

"Cannibalism could tell us something of the spiritual life of the Neanderthals"

The bones belonged to three men, three women, and six children

A paper published last week in US journal The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by a Spanish team that has spent the last 16 years analyzing the bones provides the first glimpse of Neanderthal social structures, prompting the question as to whether the family was murdered for ritual reasons, or whether hunger drove their killers.

When the scientists closely examined the Neanderthal bones, they found cut marks - signs that blades had been used to slice muscle from bone. The long bones had been snapped open. Scientists have found indications of cannibalism among Neanderthals at other sites, but El Sidrón is exceptional for the scale of evidence.

"The bones haven't been scavenged or worn out by erosion," says Carles Lalueza-Fox of Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, a co-author of the new paper.

But scientists did find fragments of Neanderthal stone blades. The cave held no remains of animals that might have preyed on Neanderthals; the team found only seven animal bones there - from one large browsing elk and a fox.

Antonio Rosas, a Spanish paleontologist who has been investigating El Sidrón for the last seven years, says that the growth patterns in the tooth enamel of the cave's inhabitants show clear signs of periodic "nutritional stress" - meaning starvation.

Those signs were particularly striking in the teeth of the infant just after it was weaned and in one of the adolescents, whose teeth showed evidence of a condition called dental hyperplasia, which is known to result from, among other causes, severe malnutrition.

But starvation may have been only one explanation for cannibalism, says Rosas, because it is also possible that the Neanderthals in the cave resorted to the practice just to complement their meager diets, and did so as part of some obscure and still unknown ritual.

"Those signs of cannibalism could tell us something of the spiritual life of the Neanderthals," Rosas says, "but more research is needed." As the investigators examined bone fragments, they tried to match them to each other. Some loose teeth fit neatly into jawbones, for example. "The whole thing was quite complicated. In fact, it was a mess," says Lalueza-Fox. He and his colleagues eventually identified 12 individuals. The shape of the bones allowed the scientists to estimate their age and sex. The bones belonged to three men, three women, three teenage boys and three children, including one infant.

Once the scientists knew who they were dealing with, they looked for DNA in the bones. Lalueza-Fox and his colleagues have published a string of intriguing reports on their genetic makeup. In two individuals, for example, they found a gene variant that may have given them red hair. They launched an ambitious project to find DNA in the teeth of all 12 individuals. In one test, they were able to identify a Y chromosome in four.

The scientists then hunted for mitochondrial DNA, which is passed from mothers to their children. They looked for two short stretches in particular, called HVR1 and HVR2, that are especially prone to mutate from generation to generation. All 12 Neanderthals yielded HVR1 and HVR2. The scientists found that seven of them belonged to the same mitochondrial lineage, four to a second, and one to a third.

Lalueza-Fox argues that the Neanderthals must have been closely related. "If you go to the street and sample 12 individuals at random, there's no way you're going to find seven out of 12 with the same mitochondrial lineage," he says.

All three men had the same mitochondrial DNA, which could mean they were brothers, cousins, or uncles. The females, however, all came from different lineages. Lalueza-Fox suggests that Neanderthals lived in small bands of close relatives. When two bands met, they sometimes exchanged daughters.

But Lalueza-Fox's hypothesis has not been entirely accepted by all in the scientific community. Linda Vigilant, an anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, considers the research "a nice start." She challenges Lalueza-Fox's claim that the Neanderthals must be immediate family because they belong to the same mitochondrial lineage. In her own work on wild chimpanzees, she finds that some chimpanzees with identical HVR1 and HVR2 are not closely related.

Lalueza-Fox says that much more research is needed. "Our findings have given us some promising clues about the demography and behavior of a species closely related to our ancestors, and that may yield information that helps us understand the factors that led to their extinction," concludes Lalueza-Fox in the article.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.