"Berlusconi wants absolute power "

Italy is mired in mud. The head of government, Silvio Berlusconi, has decided to attack anyone who still dares to criticize him, and it looks like he means to take no prisoners. The first victim of his autumn offensive, which is being waged in the courts and in the media, was Dino Boffo, the editor of Avvenire, the bishops' newspaper. Boffo stepped down on Thursday after the Berlusconi-owned Il Giornale aimed a fierce attack against him based on an anonymous report charging Boffo with being homosexual.

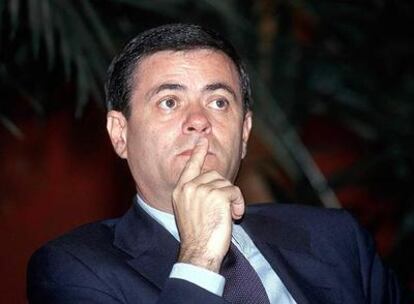

Ezio Mauro, 60, has been the editor of La Repubblica since 1996, and he has already suffered both sides of the Berlusconi offensive: on one hand, the prime minister filed a legal complaint against the newspaper for the 10 questions that La Repubblica has been asking him in print since May regarding his relationship with minors and prostitutes. On the other hand, Il Giornale has been trying to discredit Mauro personally by accusing him of tax evasion on the purchase of his Roman home. Mauro has proven the charges to be false, and says that Berlusconi has embarked on a strategy of "media bullying to send out a dual threat: one to the Church and another one to newspaper editors."

Question. Boffo was the first victim. Do you think there will be more?

Answer. Boffo has suffered a fierce and extremely violent personal attack for criticizing the head of government. His resignation proves that the strategy works: the victims are isolated, silence descends on them, nobody volunteers the name of the person behind the attack, and the level of fear increases. Boffo is only guilty of responding to the letters from priests and Catholic parishioners demanding that the Church explain its lukewarm reaction to Berlusconi's behavior. He did so prudently and discreetly. In exchange for that, Il Giornale dug up an old story published years ago by Panorama, another Berlusconi publication, to send out two messages: the Church is being invited not to criticize the premier, and other newspaper editors are being told to walk with their eyes down and talk about something else.

Q. It sounds disturbingly like a witch hunt.

A. It is a grievous case of media bullying based on apocryphal evidence: they published an anonymous note as though it were an annex to a legal record, and used it to accuse Boffo of homosexuality. But political responsibility lies with the head of government, who has embarked on a new abuse of power as a politician, as a person and as an owner in order to destroy his critics. This story demonstrates the relevance of our ninth question: Has the head of government used, or is he using, the secret services against witnesses, judges and journalists? The facts speak for themselves.

Q. Does he not think that attacking the Church can work against him?

A. Berlusconi attacks the Church because he perceives his own power as being absolute and outside anyone's control. This logic prevents him from debasing himself with things like respecting the agreements with the Church or apologizing. He would rather put on a show of strength, extend the feeling of fear, and eventually sit down to negotiate. The breach with the Church will no doubt increase the rift I talked about after the European elections. His lies about his relationships with women have cut Berlusconi off from the country and from reality. We will see how big the breach gets in the future. It will be difficult for him to re-establish a normal relationship with the Church, to whom he had been a privileged ally. The Church is a master in the art of diplomacy, but it also makes a living out of rites and symbols, and it is quite familiar with the figure of the scapegoat. No doubt it will demand reparations.

Q. In the shape of laws and money?

A. Naturally, Berlusconi will bring to the table things like the living will law, more funding for private schools, restrictions on the morning-after pill and whatever else it takes. He will offer these things under the table, secretly, renouncing state secularism and demanding silence. At the same time, the campaign to muzzle all dissidents will cost him part of the moderate electorate.

Q How do you think this campaign will play out?

A. Mario Giordano, the former editor of Il Giornale, explained it before being fired: "I am leaving because I am not prepared to snoop around under the bedsheets of other newspaper editors and publishers." Which is exactly what happened when Vittorio Feltri arrived at Il Giornale.

Q. He says he just did the same thing that others are doing to Berlusconi.

A. The difference is that our investigation arose out of a public complaint by Berlusconi's wife, who stated that he spent time with minors and that he was ill, and that exchanging sexual favors for candidatures amounted to "trashy politics." Newspapers have the obligation to investigate in these circumstances. Berlusconi is the head of government, he is a public figure who refuses to answer questions; Boffo is a citizen who was massacred for criticizing him.

Q. The right holds that we are wallowing in pure gossip.

A. It is exactly the opposite of that: it is a fight for freedom. Is there a normal relationship between power and the press in Italy? Is it possible to criticize the prime minister or not? That is the issue that arises out of Boffo's resignation, out of our 10 questions and out of the legal complaints against La Repubblica, L'Unità, EL PAÍS and other foreign media.

Q. Many people in Europe are looking at Italy, the country where fascism was invented, with a blend of concern and fear of being infected. Many citizens expect the EU to do something about it.

A. I do not know what it could do, but I do know that Italy is an anomaly among Western and European democracies. Not even Nixon used these methods against the press.

Q. Do you think that the country's image has been damaged? It would seem like these days, Berlusconi's only allies are Putin and Gaddafi...

A. That is the sad truth. Berlusconi is causing very serious damage to the country's image.

Q. In any case, is not the Italian left greatly to blame for all this?

A. The Italian left bears an enormous responsibility. It has consistently underestimated the magnitude of the Berlusconi phenomenon; it never understood it or faced up to it the way it should have. When the left was in power, it was unable to regulate the conflict of interests. Now that it is in the opposition, it continues to underestimate Berlusconi.

Q. There may be something positive in all of this. Despite Berlusconi's iron-fisted control over television networks, the battle is being waged in the newspapers.

A. The political battle is still a newspapers' battle. The problem is that Berlusconi uses his own newspapers to gag his enemies. And that happens nowhere else.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.