Henrik Visnapuu - Poet for Europe

The underground friend-to-friend book exchange system had been working for years, mostly successfully. It was this way Orwell, Nabokov, Koestler, Solzhenitsyn, and other 'forbidden' authors were read. But it was different this time, because the poet was Estonian?'Henrik,' the Scandinavian version of Henry, Heinrich, Henri ... And 'Visnapuu,' the dialectal word for 'cherry tree.'

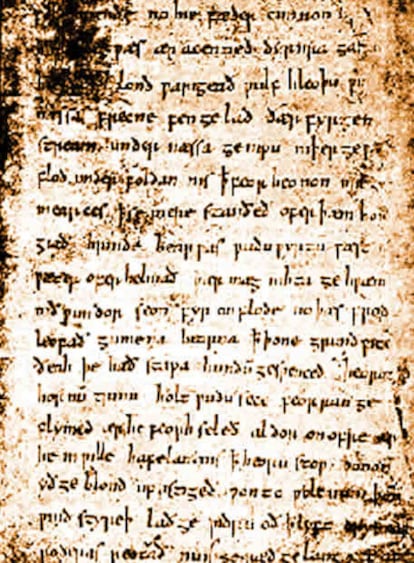

The name of Henrik Visnapuu (1890-1951) was forbidden in post-war Estonia, left out of text books and curricula, and his books were locked up in the so-called 'special departments' of libraries. Students could be thrown out of university if they were caught reading his works. In short, he was subjected to a form of damnatio memoriae, total removal of his name and work. He died in exile in the United States in 1951.

Who was he, then, and what? It was not easy for me to find this out because of the restrictions on his work, and it took years of intense research. Of peasant background, born in a small village in Estonia, Henrik Visnapuu studied classical philosophy at the University of Tartu (founded by the Swedish king Gustavus II Adolphus in 1632) and in Berlin. Later, he worked as a teacher, journalist, translator (Wilde, Balzac, Turgenev), literary theoretician, and critic. But, above all, he was an outstanding poet: a bold innovator of form, friend of Russian symbolists, and much loved by Estonian readers. Interestingly, he favoured Latin for the titles of his books?Amores, Ad Astra, Mare Balticum?as if aspiring for greater universality through the use of the one-time language of international communication, scholarship, and science all over Europe.

After World War II, when the Baltic states were forcibly incorporated into the Soviet Union, Mare Balticum, the Baltic Sea, which once connected free nations living around it, became a barrier. Its shores were vigilantly watched by gunmen ("Halt, or I'll shoot!" signs bearing their grim message), the boats of fishermen confiscated and burned on the beaches of the Baltic lands. To children growing up there, it seemed as if the sea had one shore only?nobody ever crossed it, no ships came nor went, no merry harbours. It was a lifeless sea, yet beautiful nevertheless. To quote from Mare Balticum (1948), Visnapuu's greatest poem:

Gently billowing the Baltic,

fields in breezes in Karelia.

Flowing here and in Estonia

Kalevala runos Nordic.

Our islands held like blessing

in the falling twilight dressing.

Ligo! Ligo! Heart of summer!

Wears the Daugava light necklace,

In the forest the Bear-slayer.

People work in peace and prayer.

Where the Nemunas in meadows

flows majestic through the land

to the sea, left lying Poland,

there, amid the ancient shadows

Lithuania once saw

all her glory and the wars.

Importantly, in this poem the poet treats the Baltic and Finno-Ugric peoples together, describing with a few lines the Latvian Midsummer Eve, the Bear-slayer, hero of their national epic, and the glorious past of Lithuania as the Grand Duchy, once the largest state in Europe with diverse languages, religions, and cultural heritage.

Completed in 1948 in war-torn Germany, the poem presents an urgent plea at this point, "Don't forget the Baltic states, you all,/ now before the snow of blood will fall!" By evoking the ancient Greek myth, "Once Jupiter?the divine bull?/abducted Europa, the beauty," Visnapuu addresses his appeal directly, "Listen,/ The British Commonwealth of Nations!/ Listen,/ reckless America," protesting against the plans to divide this part of Europe again (an echo of the secret protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939).

Don't Mare Balticum

and the Gulf of Finland

(never German or Russian pools!)

belong to Europe

like the coal of the Ruhr?

A shroud is spread on the corpse of the Baltic lands.

The culmination of this part of the poem comes in the next stanza, where the name 'European Union' is coined as 'Euroopa unioon' in Estonian:

Get ready for freedom

in the European Union /.../

Let's unite hands!

In all Baltic lands /.../

One thinks of the Baltic Chain of 23 August 1989, when about two million people held hands from Tallinn in Estonia through Riga, Latvia, to Vilnius in Lithuania, chanting the word 'freedom' in three languages. Mare Balticum ends on a triumphant note:

Flower of the ancient Northland

Baltoscandia, bright wreath,

on the Baltic Sea, now free.

Let the waves that wash the lone strands

in the breeze or stormy weather

band these lands at last together.

Poets have been seen as prophets throughout ages, especially in troubled times, possessing unique visions and wording these in ways that inspire masses. Freedom is at the core of Mare Balticum, the sea that after World War II separated rather than united the peoples living on its shores, where a new generation grew up who had never experienced what it meant to be free?to think , speak, write, and travel freely. What they did learn, though, was that freedom should never be taken for granted, it must be fought for and guarded constantly, always. A true poet says what is, and sometimes what will be. He does so in a tone that is pure, insistent, and intense. As Wittgenstein once put it while characterizing Trakl's poems, "Ich verstehe sie nicht, aber ihr Ton beglückt mich" ("I do not understand them, but their tone makes me happy"). Therein lies the power of poetry in what is generally regarded as our prosaic world.

Henrik Visnapuu was a poet like that?a poet for Europe and beyond

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.