Organometallic Chemotherapeutics - the Anticancer Platinums of Tomorrow?

After cardiovascular diseases, malignant tumors are the major cause of death in the industrialized world and, due to a significantly longer life expectancy, cancer-related mortality is reckoned to increase, considering that the majority of new cases occur at an age greater than 65. Early diagnosis and more effective treatment options, particularly improved chemotherapeutics, contributed to a stabilization of cancer-related mortality during the last decades despite an increasing number of registered cases. Figure 1 shows the actual values for Austria but the trend is valid for many industrialized countries.

Traditionally, two main compound classes are used in cancer chemotherapy - organic molecules and inorganic platinum-based compounds. Platinum is probably better known as a material used in the production of jewelry than as the basis for potent drugs in cancer treatment. However, the fact that metal ions are key components in many biological systems makes the approach of using metals in drugs more plausible. Nowadays, platinum-based compounds are used in 50-70% of mainstream chemotherapy regimens. The major limitations are that they are not active against all types of tumors, have considerable adverse effects and that tumors show resistance.

The success of platinum-based drugs in cancer chemotherapy initiated a steadily growing research area. Researchers are working worldwide on the development of metal-based antitumor agents, and various approaches are pursued in order to prevent or overcome resistance and to avoid side effects. In a kind of Sisyphean challenge, the process goes something like this: the synthetic chemist prepares compounds, which are tested in biological assays on their potential as an antitumor drug, and these results become the basis for further modification of the compound.

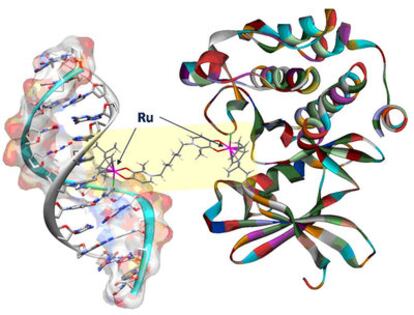

Ruthenium (Ru) complexes are one of the most promising new compound classes. After intravenous administration, they often bind to transport proteins in the blood, which in turn, act, like Trojan horses, as vehicles to the tumor. Two of these compounds, one developed at the University of Vienna and one in Trieste, are currently evaluated in early clinical studies and have shown promising results in cancer patients. Beside the clinically evaluated compounds, several drug candidates, each designed by scientists to have a desired mode of action, are in an advanced stage of preclinical development. One example of such compounds are organometallic species - we have synthesized hybrids of organic and inorganic components with a carbon-metal bond, with more than one metal center. Due to this multicenter functionality, these ruthenium compounds show different interactions with biomacromolecules in the body, e.g. DNA, in comparison to the established platinum compounds. These compounds exhibited extraordinary activity in cultures of human cancer cells and they were potent in cell lines resistant to treatment with platinum-based drugs. They have a special property, namely the ability to cross-link DNA double helices with each other or with proteins (Figure 2) and we can fine-tune this property by chemical modification. Ruthenium-based organometallics are among the most promising approaches in cancer drug development and more and more scientists recognize the versatility the compound class offers. We are now looking forward to future studies, including pre-clinical experiments, which will demonstrate the potential of these compounds in treating cancers and to complement the platinums in the clinical regimens.

Christian Hartinger, University of Vienna. www.atomiumculture.eu

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.