The town still divided over the bitter legacy of the Spanish Civil War

Opinion in Casasimarro is split about a plaque to resident killed in 1977 by neo-fascists

Casasimarro, a small town deep in the countryside of the central region of Castilla-La Mancha, was described as “extraordinarily Catholic” and “splendidly pious” by priest and linguist Sebastián Cirac in a 1947 account of the killings of members of the clergy during the Spanish Civil War. He says the community began suffering persecution before the conflict, in 1931, when Marxist militias looted and set fire to their church. According to Cirac’s account, four chapels were later burned down and the parish priest and two religious aides murdered.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, Casasimarro was in territory held by the forces of the Second Republic. Leftist militias were active in the area and killed 19 townsfolk. All the victims were Catholic and right-wing. All of them were dragged from their homes and shot dead with hunting rifles.

When the war ended in 1939, it was time for revenge. At least 22 residents were executed by supporters of General Francisco Franco’s regime after being charged with blood crimes and aiding opponents to the military uprising, leaving dozens more families in the village with bitter memories.

This all happened at least 80 years ago, but bring the subject up today in Casasimarro, it feels as if it had happened yesterday. It’s a recurring reality in thousands of villages and small towns across Spain.

A post-war wound

“In Casasimarro, people are still very sensitive about the Civil War. The bad blood over what happened is still palpable today, and it’s caused a lot of hate and suffering,” says José Luis Rodríguez, a resident. His brother Ángel Rodríguez Leal was killed in a terrorist attack on January 24, 1977, when far-right terrorists burst into the office of leftist lawyers in Madrid, opening fire.

People are still very sensitive about the Civil War. The bad blood over what happened is still palpable today

José Luis Rodríguez, resident

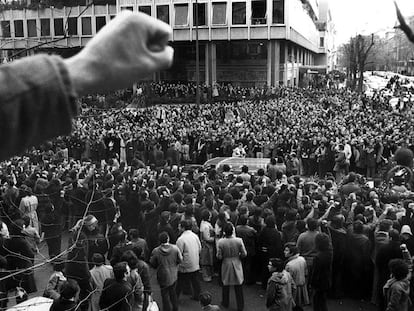

The attack, known as the Atocha massacre after the street where it took place, left five dead and four injured. It also reawakened animosity in Casasimarro, which had lost another of its sons to ideological violence.

“I remember that night I was watching the television show S.W.A.T. and I got a phone call. It was Macarena, a friend from the Communist Party, which at that time was still illegal. She told me that there had been a shooting in Atocha. I said ‘Well, my brother will tell me all about it because he’s just about to arrive.’ And she said ‘No, we have to go there now. It’s urgent,’” says Rodríguez.

The next thing Rodríguez knew, he was jumping over the police tape and climbing up to the lawyer’s office two stairs at a time. “I remember there was a trail of blood. When I was about to enter, a policeman grabbed me and took me downstairs,” he tells EL PAÍS 40 years later in a café in front of his brother’s old office. His voice is shaking.

“Afterwards people told me that my brother had been having a beer at a bar downstairs, but he’d forgotten his newspaper and went back up to get it. As soon as he got there the gunmen showed up. He opened the door,” he says, now crying.

Rodríguez says his brother was buried in Madrid but his remains were later transferred to Casasimarro, which is where he rests today under a gravestone that reads, “Ángel Rodríguez Leal, vilely assassinated by the extreme right.”

The death brought old tensions back to the surface.

“I went back to town a month later and there were people who knew me but wouldn’t even come near me. Most of them did, but some of them didn’t. Everything that had happened in the war and during the dictatorship came back with a vengeance. I think that those feelings never really disappeared in the first place.”

Whose feelings could be hurt by putting up a plaque for a victim? The feelings of the murderer?

Esperanza, resident

In 2001, the Socialist Party (PSOE) that led the town council at the time, decided to name a park after Ángel Rodríguez Leal. Council members from the opposition Popular Party (PP) did not vote for the motion and some of them, including many of the town’s residents, did not attend the inauguration. The wounds from 80 years before had not healed.

The park retains its name, and so does the controversy around it. Andrés Fernández, the only town councilor linked to anti-austerity party Podemos, floated the idea of putting a plaque in the park to the memory of Ángel Rodríguez Leal. However, the mayor and the eight city councilors from the PP opposed it, writing in a statement that the plaque “could hurt feelings” in the town.

Hurt feelings

Casasimarro, in the rural province of Cuenca, has a population of around 3,800. Its poorly paved streets are surrounded by old, low-lying houses. In the heart of the town sits a church, and in front of it is the Town Hall. On its main street there’s a big supermarket, a few banks and a handful of bars and stores. It’s January and a freezing wind whistles through the mainly empty streets. By evening there is hardly anybody out, although those who are, stop to talk and are polite and cordial.

Pepe asks not to use his real name. He owns a hardware store here. “Politics is behind this plaque business. Those people don’t really care about the boy who died, they care about something else. In fact, they already have a park named after him, so what’s the point?” he asks, greeting neighbors who cross his path. “They just want to stir things up and start a fight.”

Asked if the plaque could hurt people’s feelings, he answers: “Well, yes. Because 19 right-wing people were executed here and they don’t get any kind of plaque. Why should this guy get one, but not them? It’s going back to factions,” says Pepe.

Asked the same question, Ángel’s brother has a clear answer: “The plaque for my brother isn’t because he’s left-wing, it’s because he was a democratic victim of terrorism. We have to stand united against terrorism, and I could not care less whether the victims are on the left or the right.”

He pulls out a folder and produces the speech he wrote for the park inauguration. “You see? Here I spoke about Miguel Ángel Blanco [killed by ETA in 1997] and I didn’t care that he was in the PP, because above all else, he was a victim of terrorism.”

Esperanza, 54, agrees with Rodríguez as she clutches the collar of her jacket to protect her from the cold. “But whose feelings could be hurt by putting up a plaque for a victim? The feelings of the murderer?… I think that we need to get over these things. If someone is annoyed by a tribute to a victim because they’re from the left or the right, they have a problem.”

Manuel runs a kiosk a few meters from the town hall. He sits inside, and with a cynical smile says he doesn’t care about the plaque. “It’s fine by me whether they put it up or not, but what I can tell you is that there are people who would be very annoyed by it. Don’t ask me if that’s good or bad, but it would happen. That’s what people are like around here, so I understand the mayor.”

Juan Sahuquillo, aged 60, is the mayor of Casasimarro, which he has run with an absolute majority for the last six years. He bangs his desk with his fist and says he is “Catholic and right-wing.”

Sahuquillo explains his decision to deny the motion for a plaque to Ángel Rodríguez: “We regret the assassination of that boy but... he already has a park, and right now the town is united and calm… I don’t think it would be prudent to put it up.”

Fernández, the councilor with ties to Podemos, wanted to unveil the plaque on the 40th anniversary of the Atocha killings. Even though the town rejected his proposal, there will still be a series of events in the park that day, with left-wing politicians from elsewhere in the region in attendance. The mayor was invited too, but says he will not show up. Neither will half of the town. A plaque has also been ordered privately and will be inscribed, but will not make its appearance that day.

They take everything that we propose as a personal attack

Andrés Fernández, leftist councilor

“Our goal is to pay tribute to a victim of terrorism – the only one in the democratic history of this town. And the mayor sees it as a provocation. They take everything that we propose as a personal attack,” explains Fernández in a café near the town hall. “They think we want to relive the past. It’s actually the opposite, we want to normalize it. This didn’t even happen during the war, it happened under democracy!”

Rodríguez, Angel’s brother, accuses the mayor of lacking sensitivity.

“He still thinks along the lines of ‘my dead people’ and ‘their dead people’ or ‘He was a communist, he was a whatever’… He does not make an effort to educate people on this subject. He maintains an equal distance between the victims and the executioners to preserve the town’s unity. He doesn’t know how to do it any other way.”

A group of 16-year-olds strolling through town provide a more detached vision of history in a community still haunted by the hatred of the Civil War. Of the four of them, three hadn’t heard about the controversy surrounding the plaque. Only Rubén is aware of it and says, “I don’t understand the harm in putting up a plaque. I’m sure they aren’t doing it because they don’t have the money.”

Asked if they know anything about the 1977 Atocha Massacre, his friends turn to Rubén hopefully, but his only response is a shrug of the shoulders.

English version by Alyssa McMurtry.