“He was normal, but also a star”

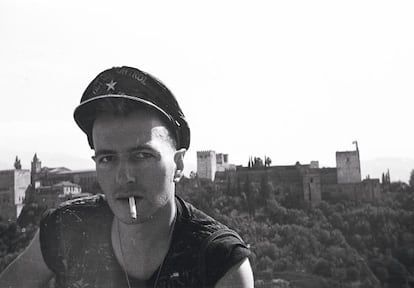

Clash front man Joe Strummer’s influence still felt in Granada after 1980s sojourn City to name plaza in singer's name this week

“I thought he was some drunk. He had his little notebook with him and he showed me the poems he had in English; I wasn’t too bothered,” recalls José Ignacio Lapido, guitarist of the long-defunct punk-rock band 091. “Then later we looked over at him and thought ‘Fucking hell! That guy looks like Joe Strummer!’ But he looked strange, a bit like a lumberjack or something. We knew the pictures of him from the Clash covers, but here? In our city?”

The disbelief was understandable. Granada in 1984 was a world away from London or New York, the late Strummer’s usual hangouts. Despite Spain’s La Movida countercultural movement gathering pace, flamenco still ruled and bands like 091 struggled to find anywhere to play in the city. There were no rock studios or bars until Silbar opened. 091 singer José Antonio García worked in Silbar at the time: “I’d been for a sandwich and when I came back they said to me ‘José, there’s a guy over there who we think is Joe Strummer!’ I said: ‘What have you been drinking? Let’s have a look!’ I went to the bar and there he was, Joe Strummer! Clear as day! But we asked him and he didn’t say yes or no. He said he was there writing, and sat jotting things down. We spent all night drinking then when the bar closed, I put on a record by a French band called Corazón Rebelde. I said to Joe: ‘You hear this band? Sounds just like The Clash, right?’ He started laughing and that was the moment when he admitted that yes, he was Joe Strummer.”

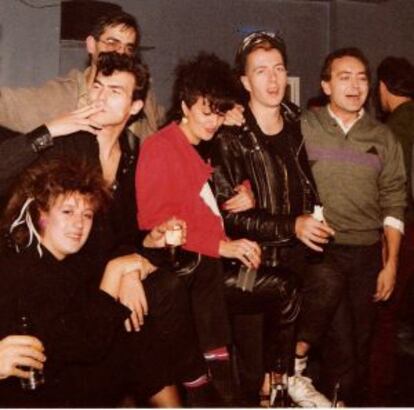

The news quickly spread. 091 bass player Antonio Arias remembers the rest of the band making him guess who they’d met: “Say a name! Go on!” knowing that never in his wildest dreams would he imagine their idol being in their local. It was to be the first of many drunken nights as their friendship was cemented. “We were all into clothes and our image so going out drinking with Joe Strummer, we were freaking out!” says Arias. “Every night was a unique experience.”

We saw the rest of the Clash in a pub and felt like shouting: 'He’s with us! He’s in Granada!'”

The band would look at each other in disbelief as they strolled around the city with Strummer in tow, looking every inch the rock star with a ghetto-blaster on his shoulder firing out his favorite reggae songs. He couldn’t have got away with this back in South London; it was the anonymity and the friends he made that drew him back time and again. The Clash was on its last legs in 1985 and although the band sensed he was fed up with things back home, he was always in good spirits. “He was the type of guy you never got bored of hanging out with, he was just fascinating,” says García. “He was just a normal guy, but a star as well.”

His knowledge of Spain’s recent history wasn’t quite up to scratch though. “He knew all about Hemingway and Orwell but not so much about the reality of the time,” says Lapido. “What he had in his mind was Franco and we had to say ‘Joe, now we’ve got a Socialist prime minister.’ He said ‘Yeah! What’s he called?’ — ‘Felipe González’ — ‘Ahh, like Speedy González!’”

091’s Arias and Tacho visited London around this time. As they passed a pub on the King’s Road they saw The Clash sat in the window, minus Strummer of course. They laughed about having heard the rumors that everyone had been desperately trying to find Strummer and the idea of strolling in and shouting “He’s with us! He’s in Granada!” was extremely tempting. But instead they left them to it. “It could have changed the course of the whole story!” giggles Antonio Arias.

Strummer loved 091’s music and ended up producing their second album Más de Cien Lobos. “He had a great ear, and knew what he wanted. He’d give us advice and play with the sound. We just loved that he was Joe Strummer!” says Lapido. Strummer rarely touched a guitar but was always playing around with ideas. “He’d change the rhythm in interesting ways; Joe was an inventive guy who was always thinking about how to improve things,” García remembers.

I loved being with him, [seeing] how he shaped the music and his lyrics"

Strummer even ended up pouring his own money into the project but they were all to be bitterly disappointed by the record label’s disastrous final mix. “The truth is we didn’t really talk about it again,” says García. “Joe felt bad about it… I asked him to sign the copy I had but he didn’t even want to do that.” Despite this disappointment, it was an experience the band would never forget. “I loved being with him, [seeing] how he shaped the music and his lyrics, hearing about his experiences,” says Arias.

When Arias fell ill with tuberculosis soon after finishing the album, Strummer gave him a piece of cardboard with a drawn-on piano. “You said you wanted to learn to play, right? Well you can start with this.” Above his piano Arias now has a poster of The Clash to remind him of his friend and inspiration. “What we miss most is his kindness.”

As Granada gets ready to name a square in Strummer’s honor this week, there can be no doubt of the effect those 1980s punk-pioneers have had on the city, which is synonymous with alternative music due to the hundreds of other bands inspired by 091. The band themselves are still as active as ever; Arias fronts Lagartija Nick and Lapido is touring the nation. García still plays regularly as well.

“It was a dream come true,” says García. “To have got to know him in such a natural way, to make a record together and share that time together. It was just incredible.”