"Juanito was asked if he wanted a brother. His 'yes' saved me from the Nazis"

Brave Belgian couple hid a Jewish boy alongside a Spanish war refugee

One was the son of Spanish Republicans fleeing the Franco dictatorship; the other, a Jewish boy who had to be hidden from the Nazis. In 1942, a Belgian family made them brothers.

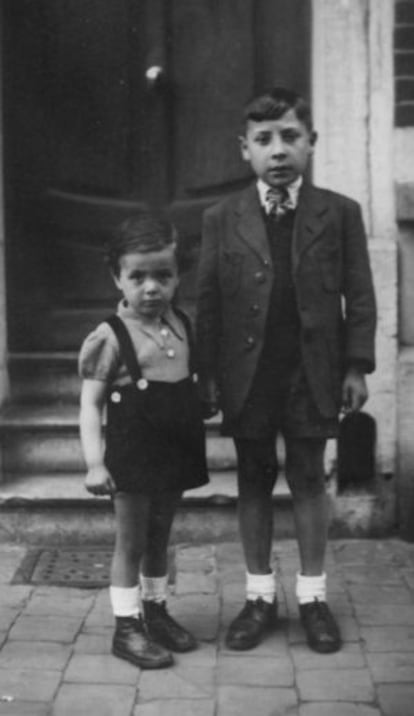

Juan Manrubia Sánchez, "Juanito," was seven when he first met two-year-old Zenon Fajertag.

"There was only one condition that the Materne family had so they could hide me in their home in Brussels: they were going to leave the decision up to Juanito, who had already been with them for two years. So my mother and I waited for three hours for him to return from school. When he arrived, he was asked: 'Juanito, would you like to have a little brother?' And he said 'Yes!' And that is how he saved my life," says the now 71-year-old Zenon, who has since changed his name to Zalman Shiffer.

"I don't know what would have happened to me if I hadn't stayed with that family. I know that a lot of Jewish children who were captured by the Nazis ended up badly."

The Maternes only had one condition: they left the decision to Juanito"

His mother, Sara, insisted on paying the Materne family for hiding her son, but they would have none of it, says Zalman. In those days, hiding a Jew could get you a death sentence but the Maternes believed it was their duty. After much insistence over payment, the Maternes accepted that Sara would be allowed to bring one egg each day from the black market.

Recently widowed, Sara had grown terrified after hearing the countless stories about what the Nazis were doing to her people. So she decided to look for a hiding place for the boy.

"Before we went to the Maternes, my mother had taken me to a convent but she thought the place was very cold and didn't want me to live there. That's when she heard about the Maternes."

Joseph and Louise Materne were a brave couple, childless and devoutly anti-fascist. The husband worked in the railroad industry and was very active in the resistance. "He would take packages of food and took part in blowing up one or two bridges," Zalman recalls. While the Maternes constantly lived in fear, Zalman never felt he was in any danger. "I wasn't aware that I was being hidden. To me, I think the worst part of that time was being told I had to write with my right hand even though I was left-handed."

In 1965 they told me Juanito had returned to Spain with his family"

Juanito wasn't the first child from the Spanish Civil War who the Maternes took in. During the period, more than 5,000 children were evacuated to Belgium; 3,350 were from the Basque Country, and two of those children stayed at the Maternes home.

"They were sent back home when 'calm' returned to the Basque Country," Zalman recalls.

And then in March 1939, Juanito came to live with the Maternes, but he didn't come alone. He arrived in Belgium with his three sisters - Paquita, Dolores and María - who were each given to different families but frequently saw each other, says Zalman. "My mother also risked her life to come and see me," he says.

When the bombing intensified in Brussels, the Maternes decided to move to the countryside, and Zalman's mother, who had been hiding out in different places, joined them.

At the end of the war, Sara, who weighed less than 40 kilos, got her son back. "It was very difficult for me to say goodbye to the Maternes. On that last day, they gave me a watch with a plastic band which I still cherish to this day."

In 1949, Sara and her son immigrated to Israel and Zalman remained in touch with Juanito until he turned 14. After that, they lost contact.

"I returned to Belgium in 1965 but they told me that the Maternes had died and Juanito had returned to Spain with his family," Zalman says. After he returned to Israel, Zalman became a renowned economist but was always convinced he would never find Juanito - he didn't even know his Spanish last names. He gave up his search.

One day two years ago, he came up with an idea of taking his search to the internet with a posting in English "Help me find Juanito." Maybe someone would be able to recognize the name or could even give him some clues as to his whereabouts.

The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation got wind of the story and became involved. Named after the Swedish diplomat who helped saved many Jews during the war, the non-governmental organization develops programs and awareness about the Holocaust.

Investigators found that the Maternes had legally adopted Juanito and he had their last name. In 1965, when Zalman visited Belgium, Juanito was still living in the house that they both grew up in. Unfortunately, he died in 2003.

"Discovering this was like a punch in the stomach. Just to think that he was in the same house, and I was staying in the same city but never saw him...!" Zalman says sadly. Nevertheless, Zalman was able to meet Juanito's three children and his sister, Paquita, who remembered him better than he did her.

This moving story about the two boys who became brothers by escaping fascism is now told in a documentary by journalist Henrique Cymerman called simply Juanito, which premiered recently at the Madrid Sephardic Center as part of a cycle of programs to promote solidarity between cultures.

"Juanito and I were part of the same thing, from the same side - those who are pursued," says Zalman.

"I don't know whether under the same circumstances I would have done what the Maternes did. But people in extreme situations do some extraordinary things."