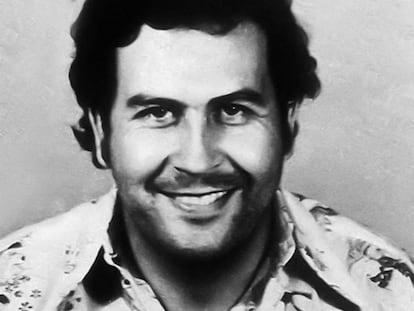

Why Pablo Escobar is anything but cool

The victims of one of the most notorious drug lords in living memory do not feel that Netflix hit ‘Narcos’ or any other depiction of him convey the reality of the damage he did

Pablo Escobar wakes up in a circular bed. He lights a joint, gets dressed and leaves his luxurious bedroom. His hit men stand behind the pink curtains. They clean their weapons, snort cocaine and feed the goldfish. One shows Escobar a story in that day’s newspaper. “Did you get rid of the bodies?” Escobar asks. The hit man nods. His boss continues on his way through La Catedral, the jail he built for his own incarceration in 1991.

Escobar was responsible for the death of 5,000 people between 1989 and 1993

This scene is from the Netflix series Narcos, which has spent the first three seasons looking at one of the darkest chapters in Colombia’s history – the focus shifts to Mexico in the fourth season. Like Escobar’s biography, the production is full of details that inject color into the legacy of a man whose culture of fear and violence dominated the country from the 1980s to 1993, when he was assassinated.

According to Netflix, more than 60 million viewers have been enthralled by the eccentric details of Escobar’s life, like his vast Hacienda Napoles ranch which was home to one of the largest zoos in Latin America. But what they were seeing was only one side of a very sordid story. The other belongs to Escobar’s thousands of victims and their relatives.

For more than 15 years, Medellín – Escobar’s stomping ground – was one of the most dangerous cities in the world. In 1991, the year the drug lord built his own prison in collusion with Colombian President César Gaviria in order to avoid extradition to the United States, there were 6,349 murders; in other words, 381 for every 100,000 inhabitants. La Catedral prison was, in effect, a luxurious estate from which Escobar ran his business with the authorities’ blessing. This was how corrupt Colombia had become.

We must never forget the damage that narcotrafficking and lawlessness did to us

Medellin Major Federico Gutiérrez

Escobar paid his hit men around €580 for each police officer they picked off. By end of the Medellin Cartel’s reign in Colombia, 550 had met their deaths in this way. In 1991, more than 100 explosive devices went off in the city between September and December. Escobar’s legacy was a river that ran with the blood of more than 5,000 victims who were killed between 1989 and 1993. Survivors do not believe that this is adequately conveyed either in Narcos or any other movie or series that has subsequently aired on the subject.

The fascination with the legend of Escobar has shifted attention away from his crimes. Frequently, the bizarre takes precedence over the tragic. Instead of looking at the damage he caused, the focus is on the fact that a town in the drug-infested region of Antioquia has the biggest concentration of hippopotamus outside of Africa – animals that, having escaped from Escobar’s ranch, were left to roam wild instead of being transferred to a zoo. Or the odd anecdote of Escobar giving his daughter a unicorn for her birthday, fashioned from the severed wings of an ostrich and a horn nailed to a live pony, which died within days. Or the soccer matches with players from Colombia’s national team. Or the parties where the piñatas were filled with dollars.

In the streets of Cartagena, street vendors still make a buck selling t-shirts emblazoned with Escobar’s image. Narco-tours in Medellin may be less popular then they were but they still attract their share of tourists. And the Spanish speaking communities outside of Colombia have adopted the roster of insults – such as malparío, hijueputa, gonorrea – that fans of the Netflix show will be familiar with.

Escobar paid his hit men around €580 for each police officer they murdered

In the Puerta del Sol in Madrid, Christmas 2016 was ushered in with a controversial billboard from Netflix that made reference to cocaine, as part of the promotion of the second season of the show. The company was forced to remove it after the Spanish authorities received complaints from the Colombian government.

In the face of this glorification, Escobar’s victims’ are seeking truth and justice and a balanced account of what really happened. Pablo Escobar ended up controlling 80% of the world’s cocaine market. Almost 30 years later, Colombia is still the world’s main producer of the drug. Land dedicated to the coca crop is expanding at an exponential rate, with more than 170,000 hectares planted to date, according to the United Nations. The country’s last big cartel, the Golfo Clan, controls the border areas in order to smooth the way for narcotrafficking. And former FARC guerrillas still have to prove to the authorities that they did not come to an agreement with Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, Mexico’s former drug kingpin, to finance a 50-year conflict with profits from the drug trafficking routes between Colombia and Mexico.

In 2016, Medellín was no longer ranked among the world’s 50 most violent cities. By 2017, the murder rate had fallen to 22 for every 100,000 inhabitants. “We need to remember,” says Federico Gutiérrez, the city’s mayor. “We must never forget the damage that drug trafficking and lawlessness did to us.”

English version by Heather Galloway.