Brexit: A dead-end street

The UK government is coming to realize that leaving the EU will take them to no safe harbor, particularly when it comes to Ireland

For the United Kingdom, the reality of Brexit is starting to bite. Vague political agreements have so far not been enough to reach a deal that will allow the UK to leave the European Union while avoiding a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The European Union’s chief Brexit negotiator, Frenchman Michel Barnier, has just put more pressure on London with a set of proposals from Brussels that would ensure that agreements reached in December come into effect. But the Irish question has once again been raised, and looks set to be an almost insurmountable obstacle.

Leaving the EU is not the easy and happy process Brexit supporters promised

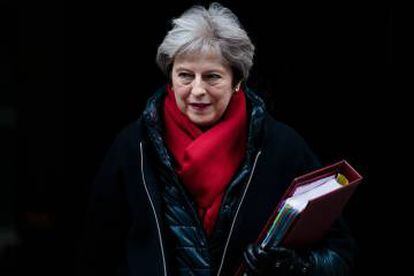

In December, the British government agreed to a proposal that would keep Northern Ireland in “regulatory alignment” with the EU after Brexit. It was a formula vague enough to be accepted. Now, the European Commission says this alignment would, de facto, imply the need for a common regulatory area of all of Ireland with custom border controls of goods brought in between the whole island and the rest of British territory. It is an option that would avoid restoring the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, but be a real loss of sovereignty for the United Kingdom. British Prime Minister Theresa May has quickly said that anyone in her position would consider this unacceptable. Brussels says the ball is now in May’s court and has called on her to find an “imaginative” solution, which is difficult to imagine because it would be like squaring the circle.

After one year of Brexit negotiations, London is now even further down a dead-end street, and it seems the UK can only come out as the loser. Accepting the cost of leaving the EU has multiplied the problems of May’s government. Internal opposition from her own party has combined with new interest in a second referendum to validate the EU agreement that the British increasingly see as negative. A new party, similar to French President Emmanuel Macron’s party La République En Marche! (The Republic Forward!), has been formed to demand a new referendum. Labor leader Jeremy Corbyn’s innovative proposal for a soft Brexit, which would keep the UK in a customs union with the EU, is another blow to May’s hard line.

May is negotiating with a bloc that continues to show a unified front on how to establish the conditions of the first desertion from the EU after more than six decades. Leaving the EU is not the easy and happy process Brexit supporters promised. Staying to some degree in the customs zone would mean accepting European jurisdiction and the negotiating difficulties have made it clear that without the European Union it would have been impossible to reach the historic Good Friday Agreements of 1998 which got rid of the border between the two Irelands and helped put a definitive end to terrorism.

London feels the territorial integrity of Britain is under threat. May has a very narrow margin to move in. She governs thanks to the unionists of the Democratic Unionist Party, who refuse to reestablish the old border. A second referendum would be a disaster for Brexit supporters. London only has one way out: to propose a flexible formula for Ireland, the kind Brussels usually devises to reach agreements, and which, of course, the United Kingdom has always criticized in the past.

English version by Melissa Kitson.