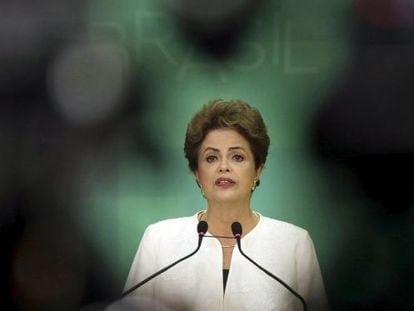

Dilma Rousseff: “They want me to resign to avoid throwing me out illegally”

Brazil’s president says the impeachment process against her is a “coup against democracy”

Five journalists from various foreign media organizations, including EL PAÍS, sat down with Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff in her office in Brasilia on Thursday. Over the last two weeks, the country has been turned upside down by the latest twists in a crisis that has seen Congress begin impeachment proceedings against Rousseff and that could see her removed from office within a month unless she is able to rally support, something that looks increasingly unlikely. “From a legal standpoint, it is very weak. This is happening because the president of Congress Eduardo Cunha [Rousseff’s enemy, even though he belongs to the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), a theoretical ally] issued a threat to the government: if we didn’t vote against an investigation into his activities, he would initiate the process. Cunha has been targeted by prosecutors after they found five illegal accounts. That is not my word, that is what the Republic’s Public Prosecutor’s office says.”

I recommend that you ask yourselves who benefits from this

Question. You have said that this process could lead to a coup.

Answer. We in Brazil have had military coups. In a democratic system, the method of the coups changes. And an impeachment without any legal basis is a coup. It breaks the democratic order. That is why it is dangerous.

Q. How would you react to a defeat? What will you do if you lose?

A. In a democracy we have to respond democratically. We will use every legal means at out disposal to make clear the nature of this coup. But I would recommend that you ask who benefits from this, many of whom have not yet even appeared on the stage, but they are there, behind the scenes. As with the case of the leaking of the conversations [between herself and former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, made public by judge Sérgio Moro]: you cannot do that. The correct thing to do was not to leak the recording, but to send it to the Supreme Federal Court, which has the right to investigate me. A judge cannot play with political passions. Nobody can sack him, but at the same time he has to be impartial. And then there is the resignation. They want me to resign. Why? Because I am a weak woman? No, I’m not a weak woman. That hasn't been my life. They want me to resign to avoid the bitter pill of having to overthrow a democratically elected president. They believe I must be very affected by this, confused, under a lot of pressure. But I’m not, that’s not the sort of person I am. I have had a very difficult life, and I’m not going to stop fighting now. I was 19 years old and was a prisoner for three years under the dictatorship, and prison in those days was no small matter. I fought under very difficult conditions. So I’m not going to resign, of course I’m not.

I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I trust in Brazilians’ peaceful nature

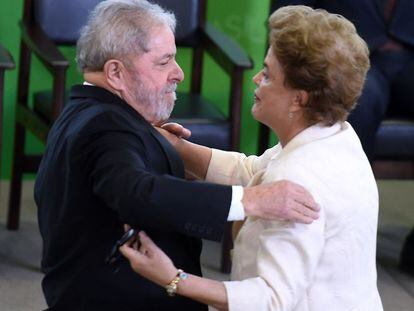

Q. Many people have criticized the appointment of Lula as a minister, saying it is just a move to evade justice through the legal immunity that accompanies the post.

A. That is part of the tactics of those who defend the idea of the worse things are, the better. And those tactics are also being used against my government and Lula was going to make my government stronger. To think that because he is a minister he can escape justice is to see a problem where there isn’t one. Let’s say this was true, that he has come here for protection. What a strange kind of protection, I would say, seeing as he can be investigated by the magistrates of the Supreme Federal Court. They are no worse or better than a judge in a lower court. The thing is that they don't want him here. But Lula is coming, as a minister or an advisor, in one way or the other, he’s coming, and nobody is going to stop that.

Q. Why didn't you choose him as a minister before?

A. I have been saying that Lula should join the government for some time now, since I began my second term in office, in 2015. He turned me down. I have always used him as an advisor. But now he wanted to join us after seeing how the crisis had worsened.

Q. You insist that you aren’t going to stand down, but isn’t bringing Lula into your government giving up some of your power?

A. Lula is my colleague. I helped him during his two terms in office. I like working with him. I am not sitting here thinking that Lula is going to steal the spotlight away from my presidency.

I have had a very difficult life, and I’m not going to stop fighting now

Q. One of the consequences of this crisis is that Brazilians have lost any faith they might have had in politicians…

A. That is a serious consequence, because in Brazil when people start to question politicians, those who want to save the country come out of the woodwork. They create chaos and then come to save us from the chaos. We are defending a pact, we defend dialogue, but this has to happen without rupturing our democracy, without unfounded calls for impeachment. We need to debate and to reform the Brazilian political system. Here in Brazil we need 14, 13 or 12 parties to support a government; for there to be stability. In most countries it is two, three or four. So we need reforms. But without a pact there will be no reforms. We’re not going to get reforms by demonstrating on the streets of São Paolo. In a series about Genghis Khan I once heard this line: “Conquering is done from a horse, governing has to be done on foot.”

Q. Are you afraid of an outbreak of violence given the mounting instability in the country and the growing polarization?

A. These outbreaks come above all from inequality and poverty. We have undertaken a major social transformation in recent years through democratic means: we have created 40 million new members of the middle class and rescued a further 36 million from poverty. We have even been able to maintain our social programs during the crisis. That’s why I don't think that the base of the country is unstable. We have no major religious differences or ethnic problems here. What is growing is political intolerance. Everywhere you look you see friends arguing, families arguing… During the demonstrations against me I went on television to say that people had the right to do anything, except to use violence. I don't know what’s going to happen, but I trust in Brazilians’ peaceful nature.

Q. How is all this impacting on you as a person, all this stress?

A. Well, I’m not getting depressed; I’m not a depressive kind of person. I don't feel guilty. At the end of the day, here in Brazil you can be arrested for having a dog or for not having one, so I don't know what the right answer is. I’m sure some people will criticize me for not getting depressed about things. I sleep well. I go to bed at 10pm and get up at 5.45am. Every day.