The DC-3 that disappeared without trace

The son of a pilot who went missing over Spain is still fighting to discover the truth about his father Stephen Whitaker believes that the CIA may have been using the plane

On the evening of October 3, 1980, Wal Davis, a US filmmaker, landed his Cessna light aircraft at Barcelona’s El Prat airport expecting to meet Harold Whitaker, who had piloted a Douglas DC-3 out of Madrid that same afternoon. Davis was supposed to fly out with Whitaker the next day to film the DC-3 as it made its way over the Mediterranean and on to Germany, alongside another historic aircraft, a Junkers JU52.

“When we disembarked in Barcelona, we were concerned, because the Douglas DC-3 still hadn’t arrived. We asked the control tower in Zaragoza for information, and they told us that the plane had taken off from Cuatro Vientos [a military air base outside the Spanish capital] half-an-hour after us. Worried about what might have happened, we decided to stay in Barcelona for the evening.”

The next day, Davis was unable to find any more information about the DC-3. “We called Zaragoza [air traffic control] but they told us that no DC-3s had crossed their airspace. It was the same story everywhere else,” Davis told the media at the time. A nationwide search was set up, but no trace of the plane has ever been found. “Disappearances of aircraft are always surrounded by the mystery that lack of information produces,” says the Spanish report into the event, a conclusion echoed by the conspiracy theories that have developed around the fate of Malaysian Airlines flight MH370.

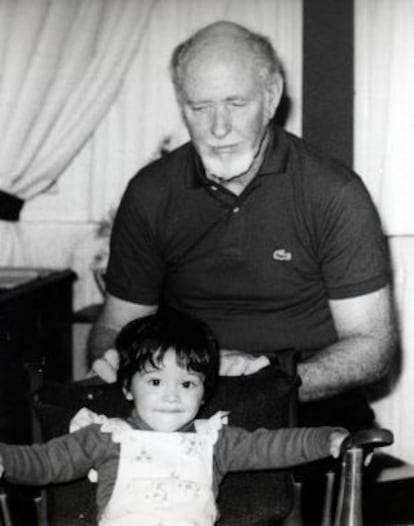

Thirty-four years later, one of Harold Whitaker’s sons, Stephen, is currently battling in the US courts to find out how a plane flown by two experienced pilots could have disappeared.

We called Zaragoza [air traffic control] but they told us that no DC-3s had crossed their airspace”

The DC-3 was bought in 1979 for the equivalent of 5,500 euros at an auction held by the Spanish air force. The new owner, a flamboyant German businessman called Günter Kurfiss, intended to add the plane to his fleet of ageing DC-3s used by Kurfiss Aviation, which has since folded. He had travelled the world buying up DC-3s, four of which crashed in one year alone, killing 14 crewmembers.

On this occasion, Günter Kurfiss had hired Whitaker and co-pilot Lawrence Eckmann to fly the plane, manufactured in 1944, to Frankfurt, where he had opened a museum called Air Classik.

The plane had been checked and some repairs were made in readiness for the flight, but a report by Spain’s Civil Aviation Accidents and Investigation Commission (CIAAC) noted: “It was not in an adequate condition for flying under the conditions required nowadays. Given that it was to be housed in a museum, a restricted aero-navigability certificate was issued,” added the report.

Whitaker had left Cuatro Vientos without authorization at 3.29pm, hoping to catch up with Davis’s Cessna, and to reach Barcelona before nightfall. His first stopover was meant to be the French Mediterranean city of Perpignan. Flying conditions were good, aside from a small patch of fog in Lleida, in the interior of Catalonia.

It was not in an adequate condition for flying under the conditions required nowadays”

Nothing is known about the DC-3’s journey, other than a report by a light aircraft that told the control tower at Cuatro Vientos that it had had to change course a few miles from the base to avoid colliding with the ageing plane. “Nothing at all is known about what happened,” concludes the CIAAC report. Despite having agreed which channel to use, Whitaker and his co-pilot made no contact with the control tower at Cuatro Vientos, Davis’ Cessna, or the Junkers.

“The accident could have been caused by them losing their way, by poor navigation equipment,” says the Spanish report. “And because no remains were ever found, it is very likely that the plane simply crashed into the sea.” Spanish military planes searched the Catalan coastline in the days after the disappearance. But the absence of any radio contact has raised suspicions that the plane did not crash.

Stephen Whitaker says that Kurfiss bought aircraft and hired out crews for the CIA. Over the years, the CIA has supplied DC-3s to rebel groups, most recently to the forces that overthrew Muammar Gaddafi in Libya.

Whitaker has asked the Spanish authorities for all the files related to the case, which in turn has turned down his request, saying that he has not provided any new evidence that would warrant reopening an investigation.

The CIA has refused to tell Whitaker if its archives hold any relevant documents pertaining to his search

For the last couple of years, Whitaker has unsuccessfully been trying to get the CIA to release its records on the disappearance of Kurfiss Aviation’s transport planes in 1980. Stephen Whitaker filed Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests with the CIA, as well as the Department of Defense and the State Department to learn if they possessed records that might explain what happened to the DC-3s.

Last month, US federal judge Collen Kollar-Kottely told the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and other federal offices to continue looking for records pertaining to the disappearance of four transport planes in 1980.

The CIA has refused to tell Whitaker if its archives hold any relevant documents pertaining to his search. The agency cited various exemptions under federal law that allow it to avoid responding to certain FOIA inquiries.

“I’m looking for a good Spanish lawyer, not too expensive, who knows about freedom of information legislation, and who can help me to access copies of all the material on file,” Whitaker told journalists last month.

He’ll need all the legal help he can get. In December, Spain for the first time passed laws aimed at formally providing access to public information. But the European Commission has noted that the planned Transparency and Good Government Committee that will administer the law is appointed by the government and endorsed by Congress, and lacks independence. It also criticizes the “scope of exceptions from the principle of access to information.” Furthermore, the law will not be fully in force until December 2015.