An Englishman in mining Andalusia

New book reveals chaplain's 19th-century stay in Spain's black country

Hugh James Rose arrived in Andalusia in 1873 as a chaplain working for British, French and German companies that were exploiting the lead mines of the Sierra Morena. But the Briton developed such a deep relationship with the country that he became a chronicler of 19th-century Andalusia — and one of the world's first travel authors — with his works Untrodden Spain and her Black Country, published in two volumes in London in 1875, and Among the Spanish People, which appeared two years later, also in two volumes.

Rose's vision has now been restored in the book Viaje a la Andalucía inexplorada. Bosquejos sobre la vida y el carácter de los españoles del interior (or, Journey to unexplored Andalusia. Sketches of the life and character of inland Spaniards), published by Centro de Estudios Andaluces and Renacimiento. It's the first time the work has been translated into Spanish (by Victoria León Varela), and it features an introduction by the British Hispanist Martin Murphy.

The work captures only a part of the four years Rose spent in Andalusia, focusing in particular on his stay in the mining district of Linares, in Jaén province, where he worked as a chaplain for the English community that then dominated the lead pits of the northern strip of the Sierra Morena.

After landing in Málaga in September 1873, Rose (1841-1878) took it upon himself to get to know the in-depth reality surrounding his work in Linares. He described the Spanish black country with great precision, including all the processes associated with lead production and their effects on the environment, as well as matters relating to the character of the Spanish miners, the high mortality rate, workers' salaries, religion, leisure time, diet and popular events, such as Carnival and Easter.

In his description of Linares details stand out, such as "the dirt, the constant noise as much at night as in the day, the taverns and the garish colors." It is an atmosphere he sums up as "lead, lead, lead," since "from morning to night you do not hear anything else spoken about, nor see anything else, other than lead."

Rose made a detailed description of the character and customs of Spanish miners in comparison to their British counterparts. Among the aspects that attract the most attention are, for instance, "the religious indifference of the character of the Spanish miner," and the loss of faith in God in exchange for faith in Providence, even though he also saw that an unwritten and non-explicit Christianity was deeply rooted beneath the surface.

"The Britons who discovered Spain in the 19th century were in general idle men, eager to explore the country they had found for the first time in the pages of the books of Miguel de Cervantes or the canvases of Murillo," writes Murphy in his introduction, summing up the special nature of Rose's work, which is so much more truthful than those of his contemporaries. "As for the Spanish language, they had learnt it by teaching themselves. Most of the impertinent onlookers who left a record of their journeys around Spain for the use of the English reading public traveled in relative comfort, observing each scene at a certain distance. This wasn't the case with Rose."

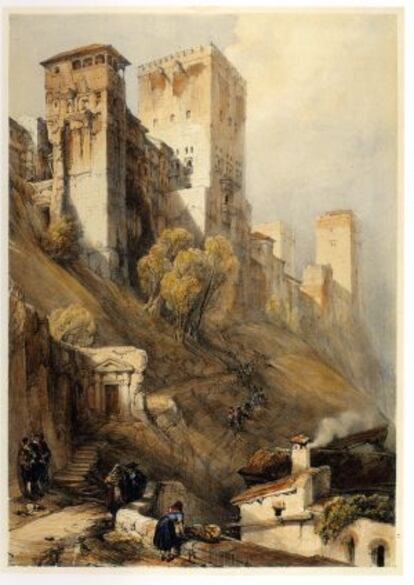

As well as his stay in Linares, Rose also speaks of his visits to the British cemeteries in Cádiz, Córdoba and Seville, along with his trips to Granada to see the Alhambra. Murphy says in the introduction that "as a journalist Rose was methodical, sensitive and observant," qualities that allowed him to compose this faithful and truthful portrait of those Spanish miners and their living conditions.