Borrowers on the point of defaulting

Loan default rates at highest level in two decades due to real estate companies

In The Company Men, a US drama that was released last year, Ben Affleck plays a company executive who plays golf, drives a good car and lives in a luxury home. But everything changes from one day to the next when he loses his job. Among other things, he stops paying for the house and soon thereafter he and his family move in with his parents.

This ease with which people in American movies and TV series interrupt their mortgage payments would be unthinkable in most European countries.

In Spain, the house is the last thing that a person stops paying for. That is why, even though overall delinquency rates have shot up in recent years and become the financial sector's number one problem, home loan default rates remain very low.

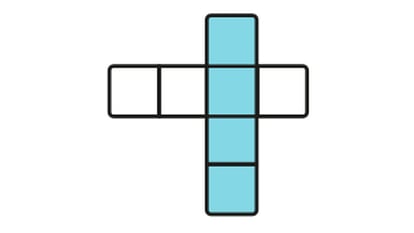

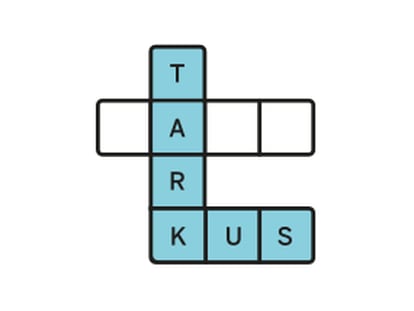

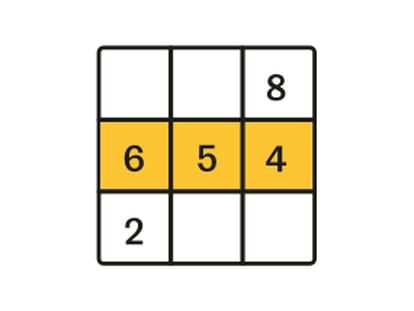

Bad loans have multiplied by 13 since the beginning of the crisis, yet just 2.7 percent of the money loaned out for home purchases is classified as bad. This figure rises to nearly 20 percent in the case of property companies.

In fact, although the volume of credit extended to individuals for home purchases is twice as large as that extended to property companies, the amount defaulted by the latter is three times greater, representing over 57 billion euros.

Companies, especially builders and developers, are chiefly responsible for a financial hole that threatens to get larger in the coming months.

The overall delinquency rate climbed to 7.5 percent in November, but experts are certain that this year it will reach eight percent, a similar rate to the one recorded in the early 1990s.

"Household delinquency rates have always been much lower than corporate rates, because Spanish legislation is very tough on personal insolvency," says Vicente Cuñat, who teaches finance at the London School of Economics.

"Despite that, it has risen a lot in recent times, and it can be expected to grow some more in the near future, when the mechanisms that have held it in check so far - unemployment benefits, personal savings and help from relatives - slowly start to run out. The banks have not yet reflected these losses in their books, but they are perfectly aware that this is going to happen," he adds.

A US citizen who sees his home lose value has an incentive to go to the bank, hand in the keys and say he refuses to keep paying for a house that is worth less than the debt he incurred to purchase it. In Spain, there is a growing demand to be able to do the same thing - in other words, for a legal figure known as deed in lieu, in which the lender agrees to forgive the remaining mortgage debt in exchange for one's deed to the home.

Many Spaniards also want this to be retroactive to benefit families facing imminent repossession of their homes.

But the Popular Party (PP) administration, just like the Socialist government before it, refuses to take that step, arguing that it would raise the interest rates on all mortgages extended by commercial and savings banks. As a result, there are no incentives to stop meeting mortgage payments in Spain.

But legislation alone cannot explain why the vast majority of a society struggling with a 22.85 percent jobless rate continues to religiously meet its home loan payments.

The alternatives offered by lenders to families in trouble also help keep the default rate down. Many banks would rather refinance the loans in the hopes that the economic situation will improve in the near future.

The problem is that lenders embraced this tactic at the beginning of the crisis, and four years later there is still no light at the end of the tunnel.

Lenders speak proudly of what they consider the strong point of their business model: while it is true that household delinquency rates on home purchases have increased more than fourfold since 2007, it remains just as true that these rates are still comparatively low.

"We have focused on commercial banking, not investment banking," says a spokeswoman at the Spanish Banking Association (AEB). "Ours is a model that has proven itself to be valid and with a solid future ahead of it. The Spanish banking sector faces the challenge of cleaning up its balance sheets, but in other countries, besides doing that, the sector also has to embrace a change of model."

The spokeswoman adds that commercial banking rules oblige lenders to maintain an extensive network of branches and to accept small transactions, and that the crisis has demonstrated that this business model works.

The other side of this optimistic outlook is represented by the more than 74 billion euros in bad loans that lenders have on their books, loans that they mostly extended to property developers and builders.

This figure would be significantly higher if it included recent foreclosures. And then there are the 17.7 billion euros that families borrowed to buy a home and which they cannot return.

Adding up all the sources, the total delinquency figure is close to 134 billion euros. Asked when they think these numbers will start going down, AEB sources declined to provide any timeframe and simply said that delinquency will decline when economic activity picks up again.

Yet the situation might be even worse than these figures would suggest. That is because to this hole in the accounts must be added nearly 65 billion euros worth of subprime loans, which stand a good risk of default even though, for now, repayment schedules are being met by the borrowers.

Some experts talk about 200 billion euros as the likely default figure in the near future.

"Most of the homes repossessed by lenders will be eventually sold, at better or worse prices. But the great black hole is the land, which cannot be turned into liquid assets," says José García Montalvo, a professor at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona.

"[Economy Minister] Luis de Guindos has said the recapitalization of the financial sector will cost the banks around 50 billion euros. Notwithstanding whether that figure is more or less exact, what I am certain of is that this money will eventually come out of taxpayers' pockets."

Families have weathered the storm so far, but it is far from certain that they will be able to keep doing so for much longer. If the delinquency rate before the crisis was less than one percent, it is now 2.7 percent and growing. The recent forecasts by the International Monetary Fund and the Bank of Spain, both of which predict a strong contraction of the economy this year, simply add fuel to the fire. The ferociousness of this recession may yet make the early 1990s crisis seem small by comparison.

Unlimited liability for households

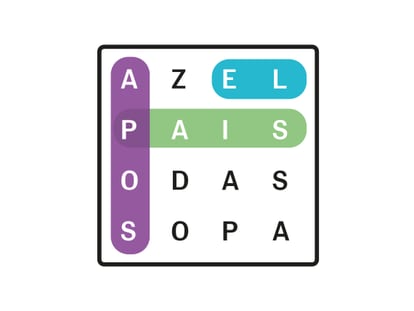

The deterioration of the economic cycle and its effect on economic agents through lower company revenues and lower family incomes also has a direct impact on growing delinquency rates, both at the commercial and banking level.

However, a detailed analysis of its evolution underscores the differences when this delinquency is broken down by types.

Except for countries that have experienced situations of extreme stress - such as Hungary and Greece - the overall delinquency rate has behaved similarly across the board.

But broken down by types, Spain turns out to show the greatest discrepancies. The country currently has a default rate of nearly 20 percent if you look at the loans extended to real estate builders and developers, yet lower than three percent when the borrowers are families. As a matter of fact, if to real estate delinquency we added all the real estate sector's assets that have been repossessed by lenders, that rate would be upwards of 30 percent.

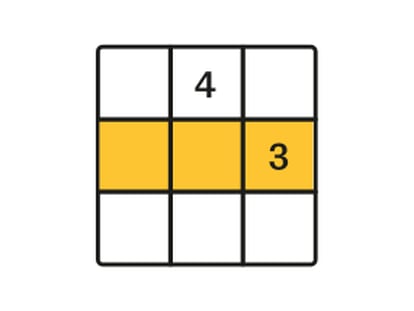

The figures are staggering. If we include repossessed assets, then it emerges that developers and builders are responsible for 73 percent of Spain's delinquency rate, even though they only represent 23 percent of all loans. Meanwhile, mortgage default by households only represents eight percent of the total, even though households are the recipients of 35 percent of the loans.

When analyzing this imbalance, it is a good idea to take legal, socioeconomic and financial considerations into account. In fact, one of the most relevant causes of reduced household delinquency on home mortgages is the fact that borrowers face unlimited liability. As a result, besides the home, all of the borrower's personal assets may be used as a guarantee of repayment - a fact that certainly conditions households' behavior. Additionally, the financial characteristics of these loans - variable interest rate, long amortization periods, loan amounts below appraisal value - have enabled lenders to restructure the mortgage whenever necessary and make repayment easier for the borrower.

Another noteworthy characteristic is the distribution of mortgage debt among Spanish families. Everyone knows that housing carries an enormous weight as a savings asset, representing 89 percent of total household wealth compared to 65 percent in the United States. And yet only 35 percent of Spanish homes are mortgaged, compared with more than 50 percent in the US.

From this starting point, it is necessary to analyze the possible impact on delinquency rates of the evolution of real estate prices and family incomes. And this is where significant differences with other countries emerge. In the case of Spain, it is not likely that a deterioration in asset value will mean higher default rates, basically because making up for falling income by remortgaging the family home is not a common practice in Spain, as it might be in the US. What may, however, play a relevant role is the evolution of household incomes.

Overall, mortgage payments represent an average 19 percent of household income, but there is a huge disparity among households, and those with lower incomes and higher debt levels may find themselves using over 66 percent of their income to meet their loan repayments.

In conclusion, the current status of loan delinquency in Spain shows that real estate assets are mostly to blame. The favorable response so far by households is a result of several factors, but future trends will be largely determined by economic recovery.

Alfonso García Mora is a partner with Analistas Financieros Internacionales (AFI).