Domestic violence victims who don't want protection

Under Spanish law, all men guilty of domestic violence must be handed a restraining order; European legal advice says the woman's view should be heard

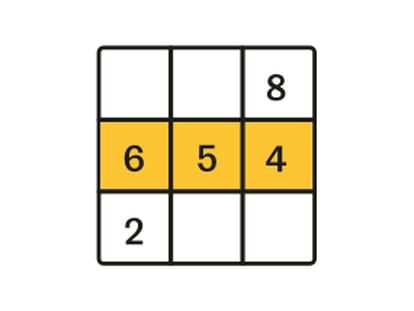

Between 2006 and 2010, 343 women were murdered in Spain by their current or former partners. Of these, 60 theoretically enjoyed some degree of legal protection against the assaulter, although in 20 cases the restraining order was broken with the victim's consent. It is not as odd as it sounds. There are couples who move back in together for a number of reasons, even after the complaint has been filed or the sentence handed down. Spanish legislation imposes a restraining order by default in all guilty verdicts in connection with domestic violence.

This forced separation, whether the victim wants it or not, was incorporated into the Penal Code in 2003 and has been hotly debated, although the Constitutional Court endorsed it in 2010. Earlier this month, the European justice system took its own view on the subject when it determined that EU legislation cannot regulate whether restraining orders must be automatic or not, but that judges should in any case listen to the victim's point of view and take it into account.

Juliane Kokott, advocate general at the Court of Justice of the European Union, replied thus to inquiries by the Provincial Court of Tarragona regarding two cases in which the victims moved back in with their batterers even though the latter had been convicted and had restraining orders against them. In both cases, the orders had been handed down against the wishes of the victims, who said they and their partners had resolved their differences. Faced with these facts, Tarragona judges wondered whether Spain's Penal Code might contradict EU law when it comes to respecting private and family life, since the victim's opinion is not currently being taken into account.

But Spanish legislation is not in breach of European rules. Lacking a specific EU ruling on the issue, which is due out in a few months, Kokott said in her preliminary conclusions that community law cannot concern itself with aspects of victim protection such as the type or duration of the sanctions against the assaulter. The advocate general, whose judgments coincide with those of the EU Court of Justice in 80 percent of cases, holds that the automatic restraining order can be "very severe" and may create a conflict between state action against domestic violence and respect for individuals' private lives. Nevertheless, she holds that this is a matter for national constitutional law, not the EU.

Spain's Constitutional Court, acting on numerous requests by local and provincial courts, ratified the system in October 2010: in order to protect a woman's life, she can be forcibly separated from her assaulter if needs be, the judges ruled. Kokott's argument that the victim should be heard makes sense to Ángela Cerrillos, president of the Themis Association of Women Jurists. "The victim must always be listened to; it's another question whether her opinion will be determining or not. The court must have the final word," she says.

Listen to the victim although her criteria cannot be binding, says the EU. For many people, this is a controversial point. Inmaculada Montalbán, president of the Observatory Against Gender Violence of the General Council of the Judiciary (CGPJ) insists that restraining orders should not be handed down automatically. "This forced measure can create undesirable situations and create further damage between two people who may still be joined together by family and social ties," she says.

But the lawyer Consuelo Abril disagrees. "Let us not forget that sometimes the victim is in no condition to give a view on her own relationship with her batterer," she says. "There are cases of emotional and economic dependence. We cannot ask the state to be responsible for victims' protection and then not have it protect those who, because of their vulnerability or state of dependence, decide to reject the restraining order against their abusers."

Even so, Abril thinks it is "useful" for their opinion to be heard, adding that many problems and undesirable reconciliations could be avoided if a group of experts were tasked with explaining the reasons behind the restraining order to the victims.

Since June 2005, over 145,000 men have been convicted of abusing their partners in Spain.

"We all make mistakes"

Eva C. R., 46, says she was on the verge of breaking up with her partner of six years after he beat her up brutally. Although she reported the assault, she decided to give Magatte G. another chance. By then, however, the judge had handed down a restraining order forbidding them from living together until 2012. Eva asked the judge to repeal the order, but her request was denied.

But the woman was adamant, and the couple moved in together until the police arrested Magatte for breaking the order. Eva's insistence in court, and other similar cases, have forced the EU Court of Justice to determine that Spanish justices must listen to the victim's opinion before deciding on a restraining order. This opinion, which is not binding for member states, will in any case not affect Eva. She will continue to live with her partner illegally, and asserts that now, after the beating, they are now closer than ever.

The assault took place in the summer of 2007, after Magatte had been out drinking after the couple had an argument over their economic woes. The man beat his partner about the face and body. Then he made death threats while wielding a knife, which he stuck all around Eva - the wall, the mattress, the wardrobe. Eva says she has forgiven Magatte because he has managed to deal with his anger. She bemoans the court's judgment over one night of excesses. "We can all make a mistake once," she said.