"This is a very radical opera"

Theatrical visionary Peter Sellars unveils 'Iolanta/Perséphone' at Madrid's Teatro Real

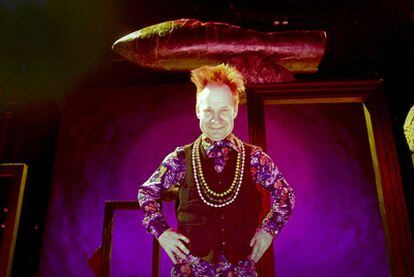

Peter Sellars ? the inventor of a large part of what has been imitated on stages around the world in recent years, and the first director to move Don Giovanni to Harlem and The Marriage of Figaro to a Manhattan apartment ? is elated to meet his interviewer.

"Very happy," he stresses, even though it is the first time he has heard the name. He hugs this reporter and holds him tightly, and repeats the act of affection with the photographer, the director of the Teatro Real, the lighting technician and the head of press... Everything is happiness and light three days before the premiere of his Iolanta/Perséphone in Madrid on Saturday.

It's an undertaking that fuses works by Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky and is commanded from the pit by Greek conductor Teodor Currentzis. "It is an enormous project, the most ambitious I have ever embarked upon," says the Pittsburgh-born director, sitting in the stalls as the colors of the spectacular set mutate. "It's madness, because it involves many worlds, and discovery for everyone."

It was just a matter of time before Sellars ? slight, energetic and faithful to his nutty-professor-style hairdo, with three great necklaces hanging off him ? landed in Madrid. (He is already set to return at the end of the season with Ainadamar by Argentinean composer Osvaldo Golijov.) His relationship with Teatro Real director Gerard Mortier has been one of mutual devotion ever since they both worked together on Olivier Messiaen's Saint François d'Assise during the period the Belgian was head of the Salzburg Festival.

Today it is all about political critique for Sellars. He's angry about what is happening in his country and the collapse of the financial system. About all the damned lies it entails, he protests. It's a fraud like the one to which King René subjects his people in the Tchaikovsky opera: his daughter Iolanta is blind, but to hide her disability from her, the monarch bans them from talking about beauty, truth and light.

"And the whole world internalizes that sense of shame, of taking all the blame. Like in this crisis," he says.

"The system is the big lie, but they tell us we must make cuts in schools, hospitals... as if we were the failures. It is a very radical opera, it is the start of symbolism in Russia, of modern art, of the search for light..."

The work was written 11 months before Tchaikovsky committed suicide, and only Mahler had the vision to classify it as a "masterpiece" and direct it in Hamburg. Its author was so affected by its failure that he didn't want to attend the premiere.

But what does it have in common with Stravinsky's Perséphone that they should be put together? "It connects because it goes beyond opera theater, it is a ritual. A ceremony. It's what the next generation later went looking for. When the first anthropologists returned from Siberia and Africa to Berlin and St Petersburg they said that they had seen poems of fire, songs of earth, the rite of spring! Everything that Modernism in Europe believed. All those composers searched for something more primitive, nearer to the essence of life."

What's more, the two works use string quartets, he notes, and enter into explorations of chamber music, "a way to be able to talk about such intimate beauty."

The author of The Rite of Spring, stingy with his praise, never forgot his admiration for Tchaikovsky and the impact his works had on him.

But Stravinksy's Perséphone, written with French author André Gide, functions like a Cubist painting, combining music, dance, poetry and visual art without any one predominating "in an imperialist way."

"They started to write it in '33 when fascism was very present in Europe. The authors went in search of a foundational myth about something that could keep society united. So they arrive at the origins of Greek ritual ceremonies. And descend into hell, because that was where the world found itself then. Like now," he says.

In Sellars' version, Perséphone descends voluntarily into the underworld out of a feeling of solidarity with the underprivileged. "It's interesting to have this piece now, with people in the street protesting, with fascism returning, openly without any apology. It makes an impact."

His patience is reduced to zero when he talks about cuts and those who direct institutions. "Money has to be used for something visionary. And now we are going through a nightmare filled with technocrats without vision. The decisions are wrong. Nobody looks deeply into the future, they want to survive from day to day: that is what cats and dogs do, not humans.

"The reduction of everything to its practical use has eliminated the future. What is happening in my country in this political campaign ? it is so low! But who are these people? The art reflects this trashy, shameful and grotesque reality in which America is destroying itself. This will not end well, it is a very painful time. That's why I think art needs to search for balance and perspective."

Enfant terrible

- Peter Sellars' Mozart trilogy (Don Giovanni, Così Fan Tutteand The Marriage of Figaro) was one of the big successes of his career.

- His version of Saint François d'Assisefor the Salzburg Festival began a close collaboration with current Teatro Real director Gerard Mortier.

- His version of Ligeti's opera Le Grande Macabrebrought him into conflict with the composer, but was acclaimed by audiences.

- His first film,The Cabinet of Dr. Ramirez(1991), was a silent movie starring Joan Cusack, Peter Gallagher, Ron Vawter and Mikhail Baryshnikov.