The price of hate in Denmark

Laws that criminalize racist or xenophobic expression, created in response to the rise of Nazism, still divide the Nordic country. Now, the EU wants all of its members to have similar rules penalizing this type of discourse, which has become standard among Islamophobes and is impossible to control on the web

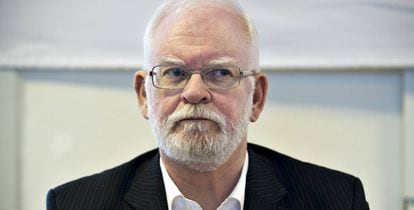

A call from an unknown number. A serious and intense voice, with a slight Scandinavian accent becomes audible from the other end of the telephone. “This is Lars Hedegaard, I believe you wanted to talk to me.” Meeting him in person is impossible. He is not in Copenhagen and he cannot specify his whereabouts because he is under police protection. Hedegaard, a 74-year-old Danish historian and journalist, is a harsh and well-known critic of Islam.

In 2011 he was recorded in his home discussing Islamic society, including saying things about how Muslim girls are raped by their fathers, uncles and nephews. He insists he was not aware of the recording, but because of it, the government fined him €700. He appealed and one year later the Danish Supreme Court acquitted him, but he became known as the man who was condemned by Denmark’s hate speech laws. What’s more, on February 5, 2013 a man who is now a member of so-called Islamic State (Isis) tried to kill him in his home.

Hedegaard says he would not take back those remarks or any of his other criticism regarding Islam, a religion practiced by approximately 4% of the Danish population. “Islam,” he says into the phone, “is not a religion; it’s a totalitarian ideology.”

ARTICLE 266B

Article 266b of the Danish Criminal Code says: “Any person who, publicly or with the intention of wider dissemination, makes a statement or imparts other information by which a group of people are threatened, insulted or degraded on account of their race, color, national or ethnic origin, religion, or sexual orientation shall be liable to a fine or to imprisonment for any term not exceeding two years.”

Basil Hassan, the man who tried to kill Hedegaard by impersonating a mailman and firing a shot at his head, did not act alone, according to the investigation. After the failed assassination attempt, Hassan managed to escape, ending up in Syria and Iraq via Turkey. The US Department of State has linked him to an international jihadist network.

Assassination attempt aside, what really bothers Hedegaard is that a judge convicted him for speaking his mind using the already old, article 266b of the Danish Criminal Code. Many simply refer to it as “the paragraph” because it is so famous. Publicly threatening, insulting or degrading people on account of their race, ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation can land someone up to two years in prison or a fine. This concept became part of Denmark’s criminal code in 1939 to stop anti-Semitic harassment. Today, it is mostly applied to cases related to Muslims. It is controversial because, according to its critics, it is incompatible with freedom of speech. The debate has also changed since the law’s inception because the most common platform for these kinds of comments has shifted to the more visceral and ungovernable space of the internet. Now, using 266b to govern Denmark’s online world is like cracking an egg with a sledgehammer.

Islam is not a religion; it’s a totalitarian ideology Danish journalist Lars Hedegaard

Despite that, the European Parliament is currently working to strengthen hate speech laws in its revision of the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD). Denmark is its model. However, the text of the European directive, still not finalized, aims to be more concrete – public incitement to violence or hatred against a group of people must be penalized.

A LAW AGAINST RADICAL IMAMS

When the topic of radical discourse is discussed in Denmark, the name Abu Bilal Ismail often comes up. In February of last year, a hidden camera from television station TV2 filmed one of his sermons at the Grimhoj mosque in the city of Aarhus. Among other things, he preached about stoning adulterous women. Two years later, Ismail was caught in another recording, this time calling for the destruction of the Jews. These kinds of speech have led to the Danish Parliament recently passing a new law (Law 18) that makes provisions for fines or up to three years in prison for “religious authorities.”

Denmark is the country of happiness. From its welfare state, to full employment, from a strong economy to the concept of hygge, or enjoying the little things in life, whether it be some beers with friends while watching the Danish handball team or snuggling up with a cup of hot chocolate at home, with a little lamp in the window. That is life and everything else is a bonus for this small and rich country, home to a population of only six million. But Denmark is also dialogue. Governments are consensus-based, there are no majorities (the current conservative government, headed by Lars Lokke Rasmussen is a coalition of three parties) and debate is a tradition. People can say what is on their mind.

The Danish Parliament, or Folketing, in the capital city of Copenhagen is a great place to see this in action. Kenneth Kristensen Berth is a deputy from the right-wing Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti), the country’s second most powerful group. In 2003, a judge used article 266b to sentence him to two weeks in prison for racism, although he never had to spend time behind bars. His crime was distributing a poster that warned against a multiethnic society. It featured two individuals covered in blood and holding the Koran. The point Kristensen was trying to make, he says now, is that multicultural societies bring with them “more criminality.”

“One of our parliamentarians, Jesper Langballe, now passed away, said in a debate that it was a problem that Muslim fathers raped and even killed their daughters. He had to go to court and was convicted, even though it is a fact that honor killings exist in Muslim societies,” adds Kristensen. The idea repeats itself: Why should expression of an idea – no matter how disturbing it is – be condemned if there is “truth” behind it? Proving these “truths” is another matter.

It goes without saying that both Kristensen and Hedegaard want to abolish 266b.

Denmark is used to immigration – 10% of people in the country have an immigrant background – and to Islam. But the feeling among people is that the arrival of new immigrants or refugees has taken root in the political class and the media as a threat to the country. And from there, it’s only a small step to discriminatory discourse.

The biggest problem is with self-censorship. especially when it comes to saying what one wants to about Islam, Muslims or terrorism

Marcus Rubin, editor of newspaper ‘Politiken’

Along Stroget Street, one of the longest pedestrianized streets in Europe, near the Folketing and the city hall square, is a block full of the offices of Danish newspapers. The security at their entrances is still high, a full 11 years after the wave of protests and threats after one of these newspapers, the Jyllands Posten, published caricatures of the prophet Muhammad.

Does the law against hate speech put limits on journalists?

“No, the biggest problem is with self-censorship,” answers Marcus Rubin, the editor of the respected newspaper Politiken. “[This is] Especially [the case] when it comes to saying what one wants to about Islam, Muslims or terrorism, not from the fear that the police will come and arrest you, but instead because of fear of terrorists.”

The famous article 266b does not place constraints on the press. Sofie Allarp, columnist and editor of Radio24syv, says she is used to comments from radicals, especially online, and that condemning hate speech is part of the Danish tradition. But she warns about the current state of rhetoric in Denmark, saying “The message that immigration is only a problem and not a solution for the future is too strong.”

Section 266b of the Danish Criminal Code has been used against a diverse group of Danes. Besides Hedegaard and Kristensen, there is also the bestselling Danish-Palestinian poet, Yahya Hassan; the Danish-Iranian artist, Firoozeh Bazrafkan; the imam of Syrian origin, Mohammed al-Khaled Samha; and an unidentified youth who had to pay €280 for comparing Islam and Nazism in a Facebook post about the Salafist organization Hizb ut Tahrir. There were more sentences in the past, but if we take this last example along with that of Kristensen, more than a dozen years have passed, but the fines or convictions have not brought an end to certain kinds of discourse.

One of the most critical thinkers against article 266b works in one of the smart buildings not far from the iconic Little Mermaid statue in Copenhagen. The lawyer Jacob Mchangama directs the legal think tank Justitia. His opposition to criminalizing hate crime is clear and he proposes an interesting alternative.

There are things that you can’t say in any society because they are illegal

Rune Lund, spokesperson for the center-left alliance

“Argument, of course,” he says. “If you are against limits on freedom of speech like me, you have a moral obligation to speak up against hate speech.” He thinks that if you criminalize it, radicals win and the message gains more traction.

“Radicalization is a problem in the Danish Muslim community, but not in the Hindu or Buddhist communities; it is a fact and we have to be able to speak about it to solve it.”

If, in Denmark, there are a lot of supporters of 266b, their voices are not as loud as those who oppose it. Returning to the Folketing, Naser Khader a Syrian-Danish deputy, shares Mchangama’s vision. Like Mchangama, Khader was born in Damascus 53 years ago, and believes that open debate works better than punishment. He brings up the case of neighboring Sweden with a high level of right-wing violence, saying it is because they speak less about immigration there. Khader, a member of the Conservative Party, also says he has suffered pressure from those who condemn his vision of Islam, but he maintains his position.

“Making fun of religion, gods and prophets indiscriminately is part of Danish culture, whether it is Jesus or Moses. Why not Muhammad? Why do Muslims have to enforce taboos? If you don’t like the caricatures, don’t buy the newspaper,” says Khader.

The rejection of criminalizing hate speech hasn’t caught on, not in the streets nor in the Folketing, where parties such as the liberal Venstre Party or the opposition Red-Green Alliance, are happy with the article.

“It works as a last barrier to racism and hate speech,” says Rune Lund, spokesperson for the center-left alliance.

And freedom of speech?

“There are limitations, of course,” says Lund, “but there are things that you can’t say in any society because they are illegal.”

English version by Alyssa McMurtry.

Life in day-to-day Europe

This article forms part of a new series, which has been launched this week by EL PAÍS and aims to find out first-hand the impact that European laws and initiatives that aim to improve the lives of EU citizens.

We will be traveling throughout Europe to listen to Europeans speak, in praticular young people, with the aim of understanding how they live their European identity and how they live with the decisions that emanate from Brussels and affect their day-to-day lives.