How Franco covered up the Monfragüe dam disaster deaths

At least 54 workers were killed in the 1965 tragedy, Spain’s worst-ever industrial accident

At around 9am on October 22, 1965, most of the children in Saltos de Torrejón El Rubio in Spain’s western Extremadura region, were hurriedly finishing off their breakfasts before heading for school. The community had been built by Hidroeléctrica Española – now utility firm Iberdrola – for the families of the workers employed during the seven-year construction of two huge dams across the Tagus and Tiétar rivers in what is today the Monfragüe National Park, creating a huge reservoir.

The official silence worked: there are communities near the dams that never discovered what happened

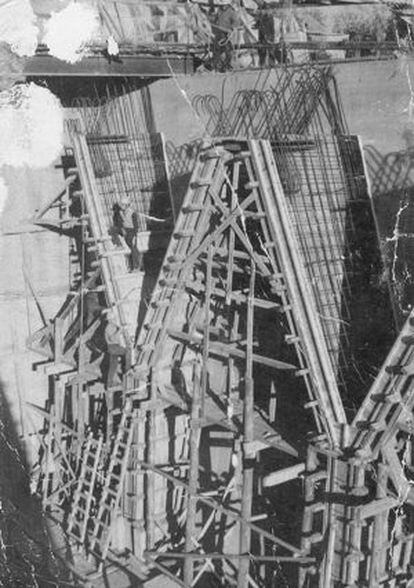

The vast project, on which around 4,000 people worked, most of them from nearby communities, involved the construction of a tunnel that linked the two reservoirs and through which water could be pumped.

The village, on the left bank of the Tagus, around 500 meters from the reservoir, consisted of shacks that had been mostly built by the workers themselves, many of whom were smallholders and day laborers who saw the project as a chance to stay in their communities rather than leaving to find work in the towns and cities, as growing numbers of people were doing at the time. On the other side of the river lived the engineers and supervisors. But all the children attended the same school, and were about to set off that fateful morning when the deafening noise of sirens and shouting prompted their mothers to take them to higher ground, fearful of what might have happened to their fathers, husbands and sons, who were about to start the morning shift.

Evacuated by the Civil Guard, the terrified families picked their way through the undergrowth on the hillsides, where they stayed until nightfall. From there they could see how the riverbed – dry a few moments before – had become a powerful and noisy torrent of water, and how on the bridge across the river and alongside it, men were moving around “like birds,” says Maricarmen Flores, who was then a child.

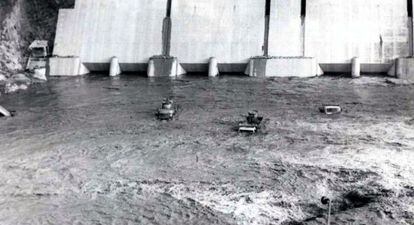

What the women and children didn’t know was that they were witnessing the worst industrial accident in Spanish history. A temporary floodgate in the 16-meter-wide tunnel had burst open as a result of the water pressure from the adjoining reservoir, flooding its interior, along with the hydroelectric engine rooms and several galleries, and drowning the men working there. Such was the force of the water that it then gushed out on to the river bed, sweeping away men there as well. Matters were made worse when the company overseeing the project was forced to open the overflow weirs to release the water from the tunnels and try to recover the bodies inside. This left the riverbed looking like a battlefield, with trucks, machinery and rubble strewn around. The official death toll was 54, while another 10 men had died in previous accidents. But the real figure was likely higher, as some bodies were never recovered.

At the time, work on the dam, which had begun in 1959, was almost finished, and they had begun filling the reservoir to test the overflow weirs. Witnesses agreed that the reservoir had been overfilled – it was just 87 centimeters from its limit – while later investigations established that the floodgate did not meet safety requirements. What was supposed to be a party – “watching the cascades of water from the overflow weirs for the first time,” in the words of one victim – turned into a tragedy that dragged on for months, and then years, as bodies continued to surface in the area (the last one appeared in 1966). And it was the workers themselves who had to take care of rescuing survivors and picking up bodies, even delivering the coffins by truck to their families.

The Franco regime imposed a news blackout on the tragedy, determined to avoid a repeat of the international and domestic coverage of the 1959 accident at another reservoir, in Ribadelago, in Galicia, in which 144 local residents drowned.

The main newspapers of the day, all controlled by the regime, published short items about the accident, highlighting the efforts of the authorities. The official silence worked: there are communities near to the site of the dams that have never discovered what happened to this day. But now, exactly half a century later, two researchers, Rosa Escobar and Inés García Herrero, have just published a book on the disaster.

The hero of the day

José Martín Malmierca emerged as the hero of the Monfragüe tragedy. The crane driver was able to pluck around 30 of his workmates from the river bed when they attached a cable to a container. He was awarded a medal by Franco, and offered a job at Hidroeléctrica’s main office in Madrid, which he declined.

The other side of the story is that of Agustín Oliva, whose family took until 2007 to find his body. It was only then that his daughters, María Victoria and Felisa, found a letter that had been sent to the local council at the time by a judge in order to inform it that Oliva’s body had been buried in a cemetery in a nearby village. The letter had been handed to Oliva’s aunt, who was unable to read.

The families of the victims were paid minimal compensation – widows received the equivalent of €120 – and only on condition that they renounced any further claims. In 1970, a local court closed the cases, despite proof of negligence provided by expert witnesses.

Some survivors were simply told that they would be compensated by being given a job.

A number of the children whose fathers worked on the project, many of whom were killed, keep in touch via an internet forum they have created. They say at this stage, all they want is for what happened to be officially recognized. “We want them to replace the plaque with the names of the dead that used to be in the old chapel at Saltos, and that Iberdrola removed without explanation,” says Paquita Martos, whose father died in the accident.