“You have to see this before you die”

A daily lottery allows a handful of people into reopened Altamira cave complex

Twelve years after the world-famous Altamira cave complex in Santillana del Mar, Cantabria, was closed to the public, a small group of fortunate lottery winners on Thursday entered the Unesco World Heritage Site to contemplate the prehistoric ceiling paintings, which were created during a period experts have placed at anywhere up to 35,000 years ago.

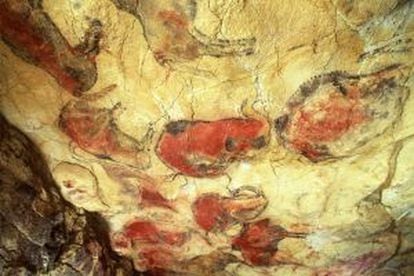

The paintings, which depict charging bison in red and black, were the first prehistoric examples in the world to be discovered.

“The paintings look like they were done yesterday,” said Antonio Díaz Regañón, a retired lecturer. Regañón was one of the lucky few to win the chance to enter the caves in a draw held the same morning at the National Museum and Research Center of Altamira, which is adjacent to the complex and features an exact replica of the original cave and paintings. Every day from now until August the same lottery will take place at the museum, allowing a handful of visitors the chance to witness the real thing.

“As a Cantabrian you have to see this before you die,” said Álvaro San Miguel, editor of the regional daily Montañés. “Today I felt the weight of history.”

It was the weight of visitor numbers that led to the closure of the caves in 2002; the effect on the walls and ceiling of human breath cold prove fatal to the paintings, which would not withstand an outbreak of bacterial or fungal spores, for example. The idea of the experiment is to gather information on C02 levels, humidity, air and rock temperature and microbiological contamination. If the results are encouraging, the complex may be reopened definitively toward the end of the year.

The exceptional state of preservation of the Altamira paintings is thanks to an act of nature. The entrance to the caves was blocked for millennia by a huge rock, which was eventually dislodged by a falling tree. The paintings were discovered in 1879 by María Sanz de Sautuola, an eight-year-old whose father was an amateur archeologist.

“I have been in twice before, 40 years ago now. It’s something you never forget,” said 62-year-old María Ángeles. “I want my daughter to go in. If my ticket comes out, I will give my place to her. We will come as often as we can until it happens.” A few hours later, María Ángeles was reduced to tears as her daughter’s number came up in the draw. Each visit to the cave lasts just 10 minutes and visitors are required to wear cleanroom suits and masks.

Gaël de Guiche, the scientific director of the Altamira complex, describes what visitors can expect of the caves: “It is pure emotion. Its impact is indescribable. In 18 months of working here I have only been in twice because it is so fragile. But the work of a conservator is to preserve the material but also to transmit its message, to share this emotion, and that is what is happening here today. Altamira is one of the three most important caves in the world and its mere existence poses very important questions for mankind and it should not be limited to just a few. I didn’t enter this profession to guard and hide this secret but to share it.”

I didn’t enter this profession to guard and hide this secret but to share it”

The caves have received several famous visitors, from heads of state to film stars, but one who had an eye for a lick of paint, Pablo Picasso, was so struck when he saw the paintings that he said: “After Altamira, everything is decadent.”

The closure of the Altamira caves in 2002 was the result of years of uncontrolled access, especially during the 1950s and 1960s. The decision was backed by the scientific community but questioned by many politicians; in 2010 the Culture Ministry commissioned a study to assess reopening the complex. It is a debate that transcends contemporary considerations. The caves do not belong to science or the regional government, but to mankind in its entirety. Can the caves be reopened without compromising this priceless piece of world heritage? Or should mankind take its lead from nature, which sealed this treasure and this preserved its integrity.

The results of allowing access could be catastrophic, but closing the caves off forever is also not a satisfactory solution.