The great priest escape

A group of clerics is seeking justice in a court action against the crimes of Franco

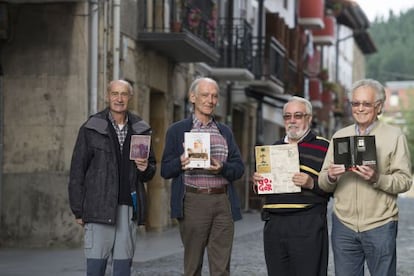

They no longer remember the last time they were inside a church, even though they were once men of the cloth. Alberto Gabikagogeaskoa, 76, Juan Mari Zulaika, 71, Julen Kalzada, 78 and Josu Naberan, 72, were all priests during the Franco dictatorship; they were also among the 100 or so inmates at Spain's only "priest prison" between 1968 and 1977.

The concordatory prison of Zamora was created to "isolate [from other Church members and political prisoners] the priests who had gone astray, those who did not want the Church to walk arm in arm with Franco, those who had been in touch with the blue-collar neighborhoods and had taken a stand in favor of the poor and the oppressed," explains history professor Julián Casanova in his 2001 book Franco's Church.

Gabikagogeaskoa, Zulaika, Kalzada and Naberan have now joined 12 other plaintiffs in an Argentina-based lawsuit against Franco's crimes. Of this group of 16 priests, only two remained with the Catholic Church after their release: Franco - Spain's leader through the grace of God - and jail combined to banish their religious calling.

"I used to go to a school run by monks. At the age of 10 they passed a paper around asking us if we wanted to enroll in the seminar. I put down 'yes.' This decision marked the rest of my life," explains Zulaika. "After that I started to have my doubts, to read about the theology of liberation... Prison pushed me out of the Church. The bishops sold us out in the ugliest way."

Prison pushed me out of the Church. The bishops sold us out in the ugliest way"

The concordat signed in 1953 between Spain and the Vatican established that priests could not go to jail. Instead, sanctions had to be served inside "an ecclesiastical or religious home [...] or at least in a different location from secular prisoners."

Several of the clergymen who ended up at the Zamora penitentiary had previously been held in custody at convents, but this solution pleased neither the regime nor the Church because it was hard to find willing hosts, and those that volunteered did not impose sufficient discipline.

Gabikagogeaskoa inaugurated the Zamora center in 1968. Zulaika and Felipe Izaguirre (who will represent all the priests at the Argentinean court in early December) were the second and third inmates.

"We were arrested in [the Basque town of] Eibar, at a demonstration. They took us to the police station and beat us with their guns. Then they transferred us to Martutene prison, stripped us and made us bend over, to humiliate us. From there we were sent to Zamora. To me it looked like a garage with bars on the windows," recalls Zulaika.

The concordatory prison was a separate pavilion of the provincial penitentiary, and the priests were kept away from the political and common prisoners. This pavilion held only clergymen, but they were not all political prisoners. "There was one priest that people said had stabbed someone; another one had helped perform an abortion; another one was homosexual," recalls Gabikagogeaskoa. "I got six months and one day for a subversive homily in which I talked about torture inside Basque prisons."

They took us to the police station and beat us with their guns"

Upon his release, in November 1968, he participated in a priestly sit-in at the Derio seminar to ask the Vatican for "a Church that is poor, dynamic and indigenous." In May 1969 he joined a hunger strike at the bishopric of Bilbao. "I was slapped with 12 years for refusing to eat for four days," he explains. Gabikagogeaskoa spent seven years inside the Zamora penitentiary.

Most of these left-leaning clergymen wound up in jail for failing to pay the fines imposed on them for participating in working class protests, celebrating Aberri Eguna (the Day of the Basque Homeland) or saying mass in the Basque language. Two of the 100 or so Church members in jail were convicted for collaborating with the terrorist organization ETA. The former prison is now an abandoned building that filmmaker Daniel Monzón used in 2008 as the setting for his movie Celda 211.

Winters were harsh - "the pipes would freeze up," recalls Gabikagogeaskoa - but the summers were even worse: "the heat was unbearable." Prison workers would wake them up at 8am. Zulaika, Gabikagogeaskoa, Naberan and Kalzada no longer remember the real names of their fellow inmates, just their nicknames. "We called one Koipe (after the brand of cooking oil) because he was unctuous; another one we called Hammurabi, because he walked like an Egyptian emperor..."

Food was bad and scarce, so they shared the items that visitors brought in. In order to pass the time, they invented a sport that they called "armball," which involved throwing a ball against a wall. They performed the Eucharist using the bread they got in jail, and some of them even began university studies, although they were never allowed to go beyond the course's first year. There was not much to read, either. "All we got was [the regional daily] El Correo de Zamora and [sports newspaper] Marca , full of holes because they cut out all the political news stories," recalls Naberan.

We collected everything we thought might be useful... until we thought about the tunnel"

"One day, the prison workers showed up wearing black armbands. They wouldn't tell us who was dead, but we found out through Marca . They'd forgotten to cut out a Celta-Barcelona match review that said there was a minute of silence over the death of Carrero Blanco [a Franco official assassinated by ETA in December 1973]."

But the best way to while away the time was to think about escape. "It is a prisoner's obligation," laughs Naberan. "It's all we ever thought about. We collected everything we thought might be useful... until we thought about the tunnel."

They decided to dig it in the laundry room because it was a locked room and the floor was covered with wood shavings. "We made a copy of the key using wax and a comb. We dug a 15-meter tunnel using nothing but spoons. It took 10 priests nearly six months. There were diggers inside the tunnel. Others collected the earth in milk cartons and slowly poured it down the shower drains. The third group kept the guards entertained through public servant psychology. For instance, with a very proud guard, we organized a ping pong championship and always let him win so he would always want to play again. Another one we kept busy with talks about birth rate control... But the days that Balzegas was on duty we didn't work on the tunnel. He was very smart," recounts Gabikagogeaskoa.

We thought we'd won, but we were taken to hospital, then right back to the Zamora prison"

It almost worked: "One day, one of the guards walked into the laundry room. We only had enough time to cover up the tunnel, but everything was full of dust. He went to get reinforcements. They thought we had a radio hidden somewhere. They couldn't believe it when they saw the tunnel. You could see the other side. The escape was scheduled for three days later," recalls Naberan. He, Gabikagogeaskoa and Kalzada took the blame so the others would not be punished.

Soon after that, the priests mutinied to force authorities to transfer them in with the political prisoners. "We burnt the mattresses. García Salve [a Jesuit and member of the Spanish Communist Party] broke all the glasses. We even threw the television set out the window," says Naberan. They were sent to isolation cells for 75 days. After that, they went on a hunger strike. "From time to time a physician would come by to scare us, telling us we would die. In the end they took us to Madrid. We thought we'd won, but we were taken to hospital, then right back to the Zamora prison."

The last one to get out was Kalzada, in March 1976. Once on the outside, they all hung up their priest's robes. "I had joined the priesthood because I thought it was the way to be idealistic. But when I was released I saw no more future in the Church. It had embraced the dictatorship," explains Gabikagogeaskoa. "There was nothing else to do."