Markets eye Spain's regional debt with caution

Local imbalances light another fire under Spain's international credibility

The newly elected premier of Castilla-La Mancha, María Dolores de Cospedal of the Popular Party (PP), has announced that she will eliminate public jobs and agencies when she takes office. The PP accuses the outgoing Socialist government of racking up over seven billion euros in debt in the third-largest region in Spain, with a population of over two million and 95 agencies funded with public money. Cospedal talked about the "excesses" of Spain's decentralized system, which devolves many powers to the 17 regional governments.

Cospedal's announcement illustrates how regional spending has become the new sticking point in Spain's strained political climate, following the implementation of unpopular austerity measures at the national level. And Castilla-La Mancha, is not even the most controversial region.

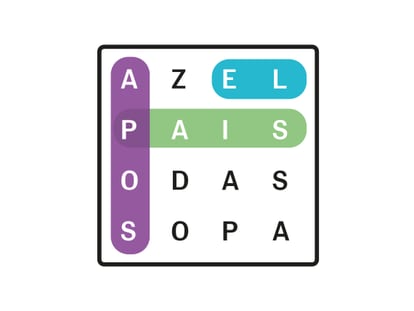

Last Wednesday, the Catalan premier had to be flown in by helicopter to the regional assembly for a heated session involving a 10-percent spending cut to entitlements like health and social services, including drastic measures like shutting down a number of operating rooms at public hospitals. Outside, other assembly members had to be escorted into the building by security forces to protect them from violent demonstrators protesting the cuts.

And despite that budget reduction, which comes on top of privatizations worth 1.85 billion euros, Catalonia says it is still unable to bring its deficit down from last year's 3.86 percent to the target 1.3 percent which Madrid is demanding of all regions, in order for Spain to meet its overall deficit commitments.

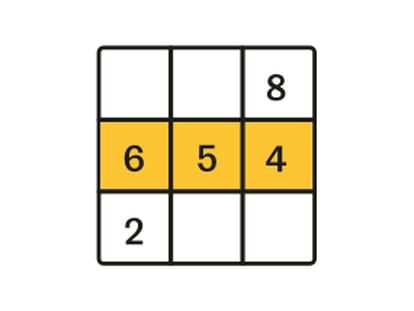

Until last March, nine out of the 17 semi-autonomous regions of Spain registered greater imbalances than expected, for a global negative figure of 0.46 percent of GDP, twice as much as in the same period last year. Meanwhile, authorities in Murcia said they will slash 3,500 substitute teacher positions at public schools; the Valencia region seems set to slim down the regional television budget and trim the number of public companies.

"The markets are in charge, but I didn't vote for them," read some of the signs seen at the recent camp-outs across Spain's city squares, where thousands of people protested the political class' handling of the ongoing economic crisis. True, nobody voted for them, yet the public administrations have borrowed nearly 680 billion euros from the markets. Over half of this debt is in foreign hands. And the public sector's financing needs for this year alone are around 200 billion euros.

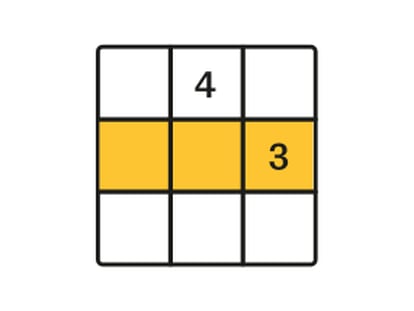

Creditors frown when they look at Spain's public accounts, especially at the regional level (national efforts have mostly earned plaudits, but with requests for further action), and they demand assurances that it is still a good idea to invest in Spanish debt. Yet there is little basis for such misgivings if one takes a close look at the numbers: regional debt remains below 20 percent of the total, and the state has enough wiggle room to make up for budgetary deviations from the target in some regions, as already occurred last year.

This is what César Miralles, director of the public sector department at the securities firm Intermoney, believes: "Since the state cannot afford to not comply with its deficit targets, it will compensate [for the regions]. There is always margin for new measures." Antonio García Pascual, chief economist for southern Europe at Barclays Capital, agrees and adds that "the central government has enough margin to raise taxes."