How maverick magnate Ruiz-Mateos engendered another financial monster

Outspoken Rumasa businessman tells investors he will pay back every euro from his homespun bond system; Spain's government says the warning signs were there

In keeping with the flamboyant public persona Spaniards have come to know over the last three decades, businessman José María Ruiz-Mateos on Friday told the more than 5,000 investors in his near-bankrupt Nueva Rumasa conglomerate: "If we don't return every euro to our investors, to the people who in a gesture of goodness and trust have lent us their savings, I will shoot myself in the head."

The pledge will have done little to calm the nerves of those investors. Speaking at a press conference in Madrid, the former Opus Dei member and father of 13 was quick to add that as a Catholic, his religion would prevent him from fulfilling his promise should Nueva Rumasa go under.

The day before, on Thursday, 79-year-old Ruiz-Mateos had filed for bankruptcy protection for 10 of Nueva Rumasa's 117 companies, in a bid to allow him to renegotiate its outstanding debt with his creditors and avoid being declared insolvent.

"If we don't return every euro to our investors, I'll shoot myself in the head"

Ruiz-Mateos has filed for bankruptcy protection for 10 of his 117 companies

Nueva Rumasa's growth strategy was to purchase firms hit by the crisis

Ruiz-Mateos now has three months to renegotiate debts amounting to 700 million euros. Otherwise, in a bizarre repeat of events which took place 28 years ago, the group will again be declared bankrupt and its assets seized. Although this time, the government has said it will not intervene. Rumasa was expropriated by the Spanish government in 1983 to save more than 60,000 jobs.

Meanwhile, the government has made it clear that the 5,000 investors involved this time have only themselves to blame if they lose their money. Economy Minister Elena Salgado said on Friday that along with the National Stock Exchange Commission (CNMV), it "did everything possible" to warn investors about the risk involved in buying Nueva Rumasa bonds.

"We changed the law, so that these emissions would have to be carried out through a broker," said Salgado, adding that the CNMV "issued up to seven warnings recommending investors to inform themselves fully" about Nueva Rumasa's bond emission and the associated risks before putting their money into the holding. She concluded: "Sincerely, I don't think that there was much more we could have done."

The investors bought Nueva Rumasa shares or promissory notes to the tune of an estimated

140 million euros. The Ruiz-Mateos family has refused to provide financial regulators with details of the amount investors have put into the company. In fact, the financial operations were organized so as to escape the control of the CNMV.

The conglomerate comprises more than 100 companies in fields including foodstuffs, tourism, construction and the Rayo Vallecano soccer club. It has over 10,000 employees. The companies are regrouped in a loose structure that does not constitute a holding company.

Nueva Rumasa's growth strategy has been based on the purchase of companies hit by the crisis, as was the case for the brands Clesa, Cacaolat Ryalcao and the Forest Agriculture Company purchased for 188 million euros in 2007 from struggling Italian dairy producer Parmalat.

In 2008 Nueva Rumasa took advantage of assets being sold by US multinational company Kraft to purchase the Apis and Fruco brands; in 2009 it purchased the H10 group, the Tranchettes, Santé and Quesillettes brands, in addition to the Carnicas Olibentinas meat producer.

Nueva Rumasa decided to launch its bond program, offering annual interest rates up to 12 percent, in early 2009. Ruiz-Mateos says that he has "rigorously" paid out all interest due since he launched his bond operation. EL PAÍS' investigation suggests that Nueva Rumasa drained 140 million euros to ''break forward'' and purchase new empty shells while the crisis strangled business and banks cut off credit.

Speaking on a Madrid radio station on Friday, Ruiz-Mateos dismissed fears that his group was about to go under. He insisted that his group was solvent and was "more than able" to repay its debts. "If not, I wouldn't have the brass neck to face you journalists. There is nothing to worry about, nothing at all."

Ruiz-Mateos instead claimed that he was the victim "of a campaign created by the banks and the media" against him, in a replay of the events that led up to the original Rumasa group being seized by the government in 1983.

The Royal Bank of Scotland, which is part owned by Spain's Santander bank, has demanded repayment of Nueva Rumasa's 36-million-euro debt, and asked that the group's assets be seized. The group also owes 45 million euros in back payments to the Social Security.

Ruiz-Mateos stopped part of its Social Security payments in March 2010. But staff contributions have been paid. The businessman has refused to comment on the backlog of Social Security payments. If after three months he has been unable to renegotiate repayment terms for his more than 700 million euros in debts, and the 10 companies that have so far sought bankruptcy protection are sold off, the banks, workforce and the Social Security would be first in line for payment, with investors and other lenders unlikely to see much cash.

"We are not going to sell off these companies; that is exactly what we are trying to avoid. This is simply a measure aimed at protecting the interests of our suppliers, customers, workers, and investors," explained José Ruiz-Mateos Rivero, the second eldest son, and CEO of the group, on Thursday. "With these measures protecting the interests of employees and investors, we guarantee the future of these companies," he continued. The CEO added that "no layoffs are planned." "We have never fired anyone and are never going to fire anyone" he assured the press.

Like his father, Ruiz-Mateos Rivero also blamed a "concerted campaign" against Nueva Rumasa, claiming that the group is valued at 5.9 billion euros, and has an annual turnover of 1.4 billion euros. But these figures are now widely discredited, and the accounting firms originally responsible say that they were based on misleading data.

According to the accounts presented to the Companies Register in 2009, dairy products companies Clesa and Dhul are the most indebted of Nueva Rumasa's companies. Clesa owes some 300 million euros, and Dhul 134 million euros. Rayo Vallecano owes 21 million euros.

The CEO said that "advanced talks" were underway with an unnamed foreign company to buy a 500-million-euro stake in Nueva Rumasa.

Ruiz-Mateos spent several short stints in prison following the seizure of his business empire in 1983, and also fled abroad briefly. The entrepreneur, who remains one of the country's richest men, even formed a political party in the late 1980s in a bid to avoid further prison sentences, winning a seat as a member of the European Parliament.

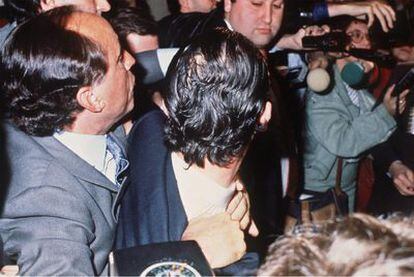

He has been waging a battle in the courts for two decades for compensation from the state stemming from the 1983 expropriation. Over the years he has regularly hit the headlines, appearing before the press dressed as Superman on one occasion and, on another, slapping former Economy Minister Miguel Boyer, who had ordered the expropriation of his company.

Expropriation and exile: the hive of dubious enterprise that won't go away

On February 23, 1983, the recently elected Socialist government of Felipe González passed a decree expropriating Grupo Rumasa, a business conglomerate comprising 18 banks and around 400 companies. This government action against the Andalusian entrepreneur José María Ruiz-Mateos aimed "to fully guarantee the bank deposits and the economic rights of third parties, which [the government] considers to be seriously under threat."

The decision was a given. A few days earlier, then-Economy Minister Miguel Boyer had told the press that he would send in Bank of Spain inspectors if Rumasa did not complete its bank audits. "Somebody wants to create an unprecedented catastrophe in the economic history of Spain," Ruiz-Mateos replied. But it was not a catastrophe - just the first major financial scandal in Spanish democratic history, besides the second most famous 23-F after the failed coup in Congress two years before that.

Early next morning, a police inspector and two officers walked into Rumasa's headquarters on Madrid's Paseo de Recoletos (now home to Barclays Bank), and took down the names of everyone who entered the building. Meanwhile, Ruiz-Mateos followed events from his home just outside the capital, and prepared his international flight.

The magnate managed to elude justice and spent several days in London before settling down in Frankfurt to await his extradition. The assets he managed to safeguard were used, years later, to create Nueva Rumasa, which is itself now on the brink of financial disaster.

On that morning in 1983, Boyer and the industry and agriculture ministers, Carlos Solchaga and Carlos Romero, explained the reasons behind the expropriation: Rumasa had become a giant conglomerate with a double accounting system. The group in fact had an overall financial hole of over 111 billion pesetas (over 667 million euros) and owed 20 billion pesetas in taxes. Its banks also concentrated a large amount of risk. Although Rumasa claimed to have profits of five billion pesetas (30 million euros), in fact it was incurring losses of nine billion pesetas (54 million euros).

The so-called "bee holding" had been a government target for a long time, but the turning point came a month before the expropriation, when the Deposit Guarantee Fund requested audits of Rumasa banks to be completed in four months at the outside. The group refused to carry out the audits, and events unfolded quickly after that. In fact, the Bank of Spain had been focusing on Rumasa since 1978 because of "the dangerous concentration of its banks' risk in its own companies and an excess of investment above orthodox levels." Ruiz-Mateos was told to disinvest.

But the businessman flatly refused. His group continued to grow and fatten up. Rumasa's flagship bank was Banco Atlántico, and the group acquired major companies like Galerías Preciados department store, the hotel chain Hotasa, wineries in Jerez and La Rioja and even the luxury brand Loewe, employing a total of over 60,000 people. Although the decision to expropriate was backed by business leaders (including the bankers Emilio Botín López, father of the current president of Santander, and Luis Valls, president of Banco Popular and a member of Opus Dei just like Ruiz-Mateos), Spain's political right took issue with it and appealed all the way up to the Constitutional Court, which threw out the appeal.

This court decision was a great political triumph for the González government and opened the way to the immediate privatization of the expropriated firms.

Meanwhile, the businessman from Jerez who began selling wines in 1961 with a capital of 300,000 pesetas barely did any jail time and prepared his bid to create a second business empire on the basis of checkbooks, lots of propaganda and few credentials.